Written by Yanis Kharchafi

Written by Yanis KharchafiSME Taxation in Switzerland: Everything you need to know about taxes

Introduction

Welcome to this new article, part of our series dedicated to entrepreneurs in Switzerland! Today, we’re diving straight into the heart of the matter: taxes… but not just any taxes. We’ll be focusing on the taxation of corporations, namely public limited companies (SAs) and limited liability companies (LLCs or Sàrls). So, if you are self-employed or operate a sole proprietorship, this article isn’t for you – the tax rules are completely different.

Why focus on “corporations”? Simply because these entities are more than just a business activity: they have their own capital, maintain independent accounting, and, most importantly, possess legal personality. This means that, for tax purposes, they are considered full-fledged taxpayers, just like individuals. They are therefore required to declare their income, pay taxes on their profits, and sometimes also on their capital.

In this article, we’ll break down the key tax principles that apply to corporations in Switzerland. We’ll start with the general rules that apply across the country, then move on to a special focus on the cantons of Vaud and Geneva, highlighting their local particularities (and sometimes frankly complex rules… especially in Geneva!).

Ready to demystify Swiss corporate taxation? Let’s get started.

The line-up:

The two annual taxes for your SME

Let’s start with the basics. To understand corporate taxation in Switzerland, it’s important to first grasp the structure of our tax system, which is based on three levels of taxation:

- The municipality where your company is registered,

- The canton where it operates,

- And finally, the Confederation, i.e., Switzerland at the national level.

Each of these entities can levy their own taxes according to common rules established by the Federal Direct Tax Act (LIFD) and the Harmonization of Cantonal and Communal Direct Taxes Act (LHID). In short:

- The canton and the municipality tax both your company’s income (profit) and capital.

- The Confederation, on the other hand, only taxes profit—there is no capital tax at the federal level.

With this foundation in place, we can now move on to the heart of the matter: calculating profit tax.

Profit Tax – How to calculate it?

The principle is simple… in theory. To calculate profit tax, you first need to determine the taxable profit generated during the relevant fiscal year.

Rather than diving into accounting concepts already covered in our dedicated article on SME accounting, here’s a brief summary, illustrated with a concrete example.

What is taxable profit under Swiss law?

It’s simply the total of all income generated by your company during the year, including:

- Sale of services

- Sale of products

- Gains from asset disposals (for example: you buy wine and resell it at a profit, or you sell a vehicle or a fully depreciated machine)

- Investment income (interest, dividends, etc.) if your company holds income-generating investments

- Real estate income: if your company owns a property, the rent collected also counts as profit

Good news: it is, of course, possible to deduct all expenses necessary for the company’s operations, provided they are justified for business purposes (and a quick reminder for those thinking of passing off a personal dinner as a business expense: the expense must have a clear business link, otherwise it will not be accepted).

Examples of deductible expenses include:

- Purchase of raw materials

- Employee salaries

- Social security contributions

- Rent for business premises

- Maintenance and operating costs

- Bank and transaction fees

- Accounting, tax, and legal fees

- Professional insurance

- Business entertainment expenses

- Depreciation

- Provisions

- Taxes and levies

- Etc.

The purpose of accounting is to record all transactions to produce an income statement that reflects the company’s economic reality. This income statement will naturally reveal the taxable profit.

From there, the tax calculation can begin.

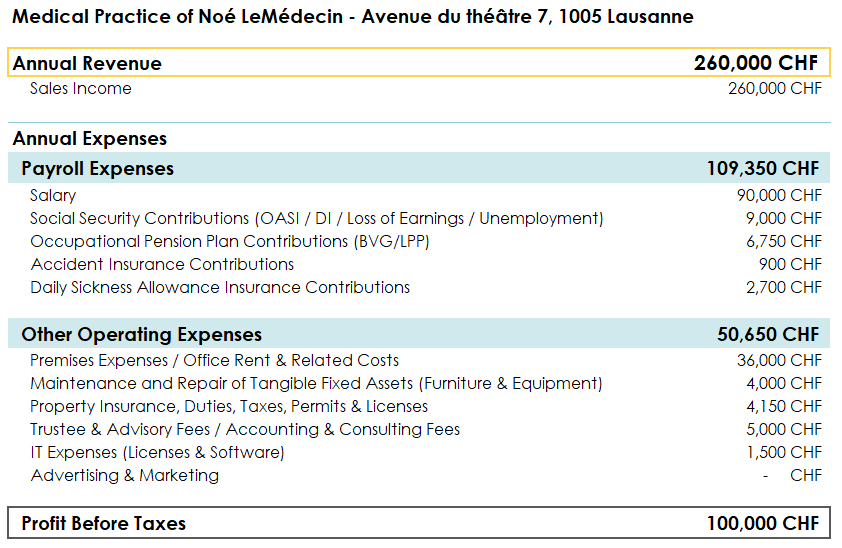

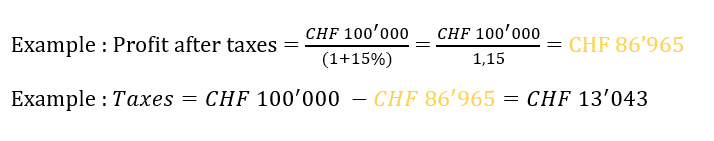

Let’s take an example: a typical medical practice based in Lausanne. At the end of the year, after deducting all expenses (except taxes), it reports a pre-tax profit of CHF 100,000.

In short, a completely standard medical practice.

The last line of the table highlights what we call pre-tax profit—the result of all invoices issued minus all the expenses you have paid. Note: this includes all expenses except taxes.

Warning: I should give you a heads-up—this is where things get tricky, and even doing my best, the following sentences may not be the easiest to follow, so hang in there. In Switzerland, the taxes a company pays are considered a deductible expense, just like any other business expense (salaries, rent, etc.). To simplify the example, let’s assume a tax rate of 15%, and we will detail the actual rates later in this article, which depend on the canton and municipality where your company is registered.

Back to our example: the tax expense to record should be 15% of profit after tax, not before tax. That’s the subtlety to understand.

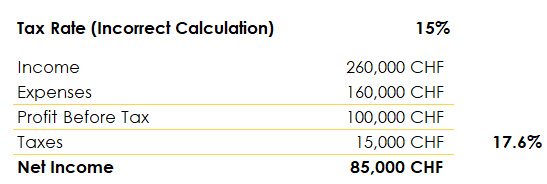

Problem: if we take our numbers and apply 15% to our CHF 100,000 pre-tax profit, the taxes would amount to CHF 15,000.

Using this completely incorrect method, the CHF 15,000 in taxes would not actually represent 15% but 17.6% of the profit after tax, which is wrong (CHF 85,000 divided by CHF 15,000).

So, how can we make the taxes truly represent 15% of profit after tax? This is where I hope your accounting-mathematical mindset is ready. To work around this complexity, we need to solve a relatively simple equation. For this introduction, I’ll skip the detailed calculation, but for those curious about this “magic formula,” feel free to get in touch.

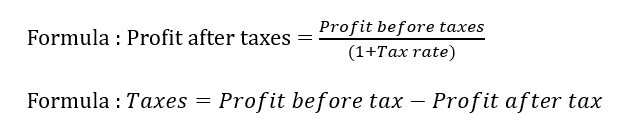

For the rest of you who prefer the shortcut, here are the two formulas to remember and apply:

Once these formulas are understood, we need to replace the variables with their actual values. Here’s what we get with our example:

Finally, the tax expense to record in the account related to taxes—which will reduce the profit of our medical practice—will be CHF 13,043, corresponding exactly to 15% of CHF 86,965.

Once the tax amount is calculated, you can finalize your company’s income statement to submit it to the relevant authorities:

I hope that, through these few lines, the calculation of profit tax is a little clearer for you. And if you still have questions, don’t hesitate to contact us at: [email protected].

Before moving on to capital tax, a few additional points are worth discussing. In Switzerland, there are other particularities that can complicate tax calculations, such as:

- Replacement of assets (selling an asset to invest in a newer one),

- Income from qualifying participations,

- Carryforward of previous losses, and

- Exempt income.

However, as long as your business remains relatively straightforward, the tax calculation should not differ significantly from what is outlined in this article.

Capital Tax: The cantonal specificity of Swiss SMEs

While profit tax affects all Swiss companies more or less in the same way—mainly because its legal basis is governed and harmonized at the federal level—the capital tax of a Swiss company presents a very different reality. It is exclusively regulated by cantonal law! And, as you may have guessed, this system works similarly to the wealth tax for individuals: differences between cantons can be not only significant but sometimes even dramatic.

This cantonal disparity is an important factor when choosing the location for your company. The same capital can be taxed very differently depending on whether your registered office is in Geneva, Lausanne, Zurich, or Lugano. Later in this article, we will take the time to specifically detail the peculiarities of the canton of Vaud and the canton of Geneva, as these two French-speaking cantons have particularly interesting fiscal characteristics worth analyzing.

Key Step – Correctly valuing your company’s assets and liabilities

Just like when calculating taxable profit, before you can seriously discuss capital tax, you must first know precisely what will actually be taxed. And even though it’s not the main focus of this article, I’d like to take a short technical detour on the crucial topic of accounting valuation, because this is what ultimately determines the exact amount of your net assets at the end of your fiscal year.

It’s important to know that Switzerland has several distinct accounting frameworks coexisting in its economic landscape (Swiss GAAP RPC, international IFRS standards, and the Swiss Code of Obligations). However, in the vast majority of situations concerning SMEs, the Swiss Code of Obligations (CO) is consistently used and applied for all tax-related matters, regardless of where your company is registered—whether in Lausanne, Geneva, Neuchâtel, or anywhere else in Switzerland.

It is this specific legal basis in the Code of Obligations that Swiss tax authorities will invariably use to validate, audit, or, if necessary, adjust your annual tax return.

Our fundamental question then becomes: what exactly does the Swiss Code of Obligations say about the valuation of company assets?

Valuation of Assets Under Swiss Law

Article 960 of the Swiss Code of Obligations clearly explains how a company’s assets should, in principle, be valued in your accounts: “At initial recognition, an asset is measured at no more than its acquisition cost or production cost.”

This fundamental rule means that in your annual balance sheet, you must always report the historical acquisition cost of an asset—or more precisely, what it actually cost you to acquire it (including acquisition-related expenses). This is known as the historical cost principle.

But the story doesn’t end there! Throughout the operational life of your company, certain value adjustments will naturally affect the book value of some assets, mainly through the mechanism of depreciation.

For a concrete example: an industrial machine purchased for CHF 100,000 will initially be recorded on the balance sheet at this acquisition cost. Over time, the machine’s wear and tear, technological obsolescence, and loss of efficiency must be accounted for. The goal is that after a number of years of service, the machine is fully depreciated to zero in your accounting books, reflecting its economic reality.

This depreciation logic applies to all your fixed assets: company vehicles, office furniture, IT equipment, production machinery, and so on.

Each asset category follows specific depreciation rates, generally accepted by Swiss tax authorities and explained through official circulars.

Calculating taxable capital – The core mechanism

To calculate the taxable capital of your Swiss company, the basic principle is remarkably similar to the method used for individuals when calculating their taxable wealth (referred to as “assets” in this context).

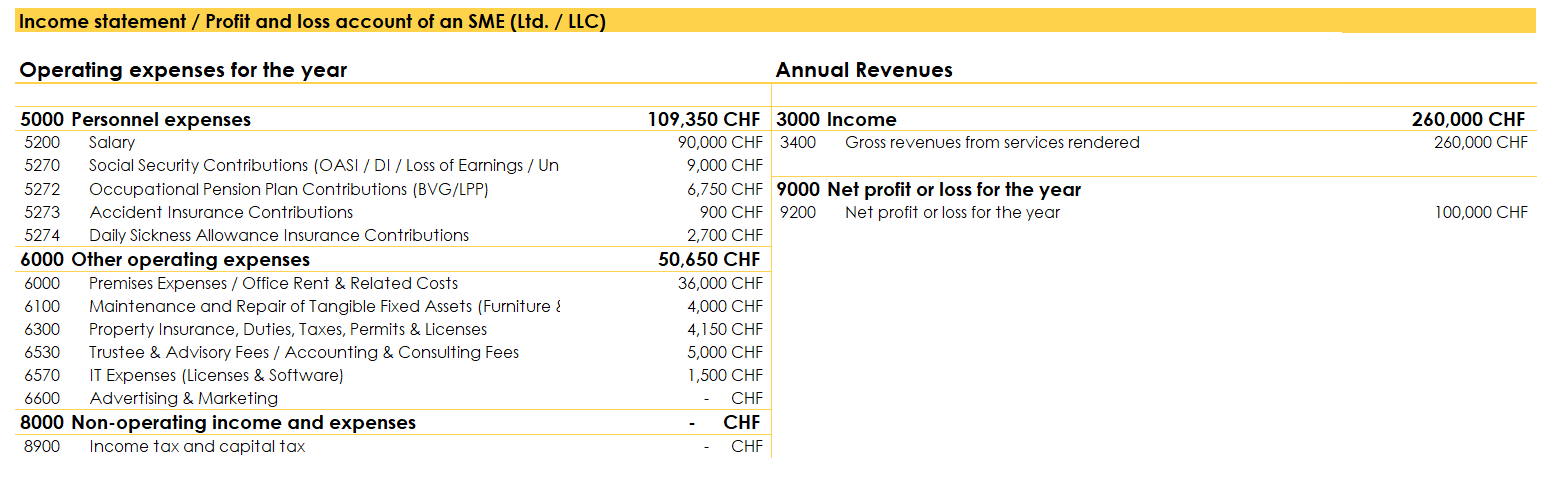

The basic formula is simple:

Taxable Capital = Total Assets (at book value) − Total Liabilities

By applying this arithmetic subtraction, we obtain what is commonly referred to in accounting as the company’s equity or shareholders’ equity. This equity represents the true value of what your company actually owns at the precise moment of the annual financial statement closing.

On the asset side, a company typically has:

- Cash and cash equivalents (bank accounts, petty cash)

- Accounts receivable (invoices awaiting payment)

- Inventory (goods or raw materials)

- Tangible fixed assets (machines, vehicles, furniture)

- Intangible assets (software, patents, trademarks)

- Investments in other companies

- Financial assets (loans granted, security deposits)

On the liabilities side, we record:

- Accounts payable (invoices to be paid)

- Social and tax liabilities

- Bank loans

- Provisions

- All other financial obligations

The result of this equation—your equity—forms the basis on which your cantonal and municipal capital tax will be calculated. This is the amount to which the specific tax rates of your canton and municipality will be applied.

A small clarification: a company’s equity can also be divided into several categories:

Share Capital – The Foundation of Your Company

This is the foundation of everything! Share capital represents the initial funds that legally gave birth to your company. Depending on the chosen legal form, the minimum required amount differs:

- CHF 20,000 minimum for a limited liability company (LLC / Sàrl)

- CHF 100,000 minimum for a public limited company (SA)

Naturally, the share capital can exceed the legal minimum if the founders decide to contribute additional liquidity at incorporation. It represents the initial financial commitment of the partners or shareholders to their company and serves as a guarantee for creditors.

Legal Reserves from Share Capital – The result of securities transactions

This slightly technical category deserves a detailed explanation. Legal reserves from share capital are primarily formed in two specific situations:

- During a capital increase: If your company issues new shares or membership interests, and these are sold at a price higher than their nominal value, the difference contributes to these reserves.

- During the sale of existing shares or interests: When a partner or shareholder sells part of their shares at a price higher than their initial nominal value, the difference between the original value (nominal value) and the transaction price goes into these legal reserves from share capital.

Concrete example: If nominal shares of CHF 100 are sold for CHF 150, the CHF 50 difference per share constitutes a legal reserve from share capital.

Legal Reserves from Profit – The prudence requirement imposed by law

The Swiss Code of Obligations wisely requires Swiss SMEs to gradually build a financial safety cushion by mandatorily allocating a portion of their annual profits. This legal obligation aims to strengthen the financial stability of companies and protect creditors.

The mechanism is as follows: Each year your company generates a profit, you must allocate 5% of that profit to these legal reserves until the total reaches 20% of the paid-up share capital.

Practical example: For a public limited company (SA) with a capital of CHF 100,000, you would gradually build CHF 20,000 in legal reserves from profit, allocating 5% of annual profits until reaching this cap.

Free Reserves – Between Statutory Obligations and Natural Accumulation

Free reserves have a dual nature that is particularly interesting to understand:

Statutory reserves

Your company may have decided, in its bylaws, to set stricter rules than those required by federal law. In this case, your statutes can require your company to allocate an additional portion of annual profits to reserves beyond the legal minimum. This approach reflects the founders’ increased prudence.

“Natural” or Accumulated Reserves

Conversely, if your company does not fully distribute the surplus profits earned in previous years (whether for strategic reasons, prudence, or simply because personal cash is not needed), the undistributed balance is automatically added to these free reserves.

These reserves often represent the largest part of a prosperous company’s equity, especially for businesses that reinvest profits rather than distributing them systematically.

Retained Earnings – Profit or loss for the current year

This component reflects your company’s financial performance over the most recent fiscal year:

- In case of profit: If your company generated a positive surplus during the year, this amount appears in equity as a positive figure, increasing the taxable base for capital tax.

- In case of loss: Conversely, if your company incurred a loss during the fiscal year, this amount appears as a negative figure, reducing the taxable base for capital tax.

This item is temporary by nature, as at the next general meeting, shareholders will decide the allocation of this result: dividend distribution, allocation to reserves, or carryforward.

For the vast majority of Swiss SMEs, these five categories of accounts constitute the main components of total equity. It is precisely on this consolidated base that cantonal and municipal authorities calculate your annual capital tax.

It is therefore crucial to understand this mechanism, because each additional franc in your equity will result in a slightly higher capital tax, according to the rates in effect in your canton and municipality of registration.

Step 2 – Methods for calculating capital tax: Simpler than it seems?

The basic principle is indeed quite similar to the profit tax we just discussed. Once your company’s equity has been calculated accurately, cantonal and municipal tax authorities will determine the specific tax rate to apply to this capital, and in theory, that should be the end of the story!

Easy, right? Honestly, in terms of general principles, this part is not the most complex of the Swiss tax system. However, before finalizing this important introduction to the general taxation of Swiss SMEs and before presenting a concrete, numerical example of capital tax calculation, it is important to highlight that there are a few technical particularities that deserve explanation, as they can have a significant impact.

Hidden Equity – When a debt isn’t really a debt

Here’s a key subtlety that Swiss entrepreneurs often encounter, and it can lead to some surprises during tax audits!

It is not uncommon, when starting a company, that the CHF 20,000 minimum for an LLC (Sàrl) or the CHF 100,000 minimum for a public company (SA) is insufficient to comfortably develop the business during its first years of operation. Faced with this economic reality, many pragmatic entrepreneurs decide to inject additional personal funds into their company.

This injection often takes the form of a loan from the shareholder or principal partner to their own company. Accounting-wise, this loan is logically and correctly recorded as a liability on the company’s balance sheet. Swiss tax authorities have developed well-established guidance on this matter. They often consider such loans as “hidden equity” or “equity disguised as debt.”

Tax reclassification: In these cases, the tax authorities simply add the amount of the shareholder loan to the company’s taxable capital, as if it were actual equity.

Common criteria for reclassification include:

- A loan with no clear maturity or vague repayment terms

- An interest rate below market conditions (or no interest at all)

- An amount disproportionate to the initial share capital

- A company that would never have obtained such a loan from a bank

Capital Tax – Theoretical but rarely applied in practice

This is perhaps one of the most important and least known subtleties of the Swiss corporate tax system!

In the vast majority of cantons we regularly advise, cantonal legislation often excludes or significantly reduces capital tax when the previously calculated profit tax is considered “sufficient” or “more significant.”

In practical terms: If your company pays substantial taxes on its annual profits, there is a very high chance that the capital tax will either be non-existent or reduced to a symbolic amount.

Step 3 – Calculating capital tax

As established, each Swiss canton has its own specific rules, but the general idea is remarkably consistent across the country: determine the company’s net equity and apply the cantonal and municipal tax rates.

But here’s where things get tricky again! We encounter the same mathematical challenge as with profit tax: tax creates a deductible expense, a deductible expense reduces equity, reduced equity lowers the taxable base… and so on, in an apparently vicious cycle!

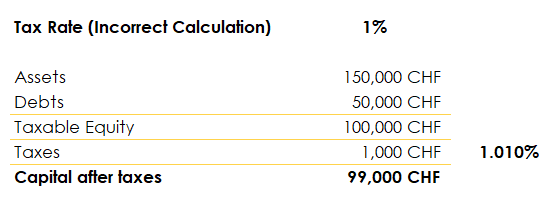

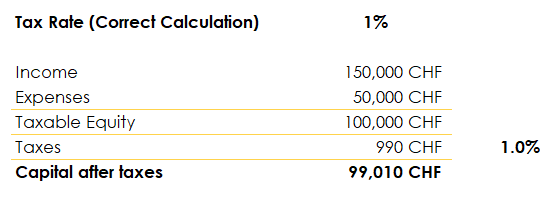

Let me explain this mechanism with a concrete numerical example. Suppose your company has:

- Total assets: CHF 150,000

- Total liabilities: CHF 50,000

- Equity before tax: CHF 100,000

Now, let’s assume the capital tax rate in your canton, including both canton and municipality, is 1%.

So, it may not be immediately obvious, but by applying this simplistic method, the effective capital tax is not 1% as intended, but 1.01%! And we want it to be exactly 1%.

We therefore need to use the same “magic formula” we developed for profit tax:

Formula:

Equity after tax = Equity before tax ÷ (1 + tax rate)

And this time, we’ve got it! The tax rate is now mathematically correct and matches the intended legal rate exactly.

There you have it! From now on, you can legitimately claim that Swiss corporate taxation is your area of expertise. You now understand the mechanisms behind the two main types of taxes affecting your SME:

- Profit Tax: based on your company’s operational results

- Capital Tax: based on your company’s net assets

This knowledge will help you better understand your tax returns and anticipate your tax liabilities.

Before closing this article—and since the vast majority of our clients are located around the Lake Geneva region—a deeper dive into the specific tax features of the cantons of Vaud and Geneva (which may take a little longer than expected!) will certainly enhance your practical understanding.

Corporate taxes for companies based in the Canton of Vaud

As you’ve discovered throughout this article, the canton of Vaud follows the general Swiss rule: your Vaud-based company will be subject to profit tax and potentially capital tax. But don’t worry—Vaud’s tax authorities have implemented a remarkably logical and fair rule, which I like to call “The Maximum Principle.”

The canton of Vaud applies a particularly intelligent and easy-to-understand tax rule, summarized as the “maximum of the two taxes” principle:

- If profit tax exceeds capital tax, only the profit tax is levied

- If capital tax exceeds profit tax, the capital tax applies

The total tax your Vaud company will pay is therefore the maximum of these two calculations. This approach prevents double taxation and ensures that you only pay the higher of the two, never both combined!

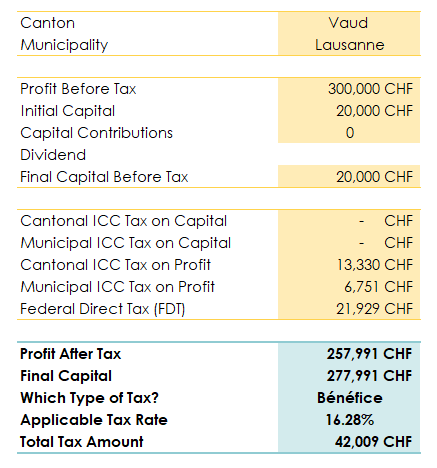

To illustrate this mechanism concretely, here are two typical examples we frequently encounter in our advisory work:

Example 1: High-Growth Start-Up – “Cutting-Edge Medicine Sàrl”

- Equity: CHF 20,000 (minimum Sàrl capital)

- Profit before tax in 2025: CHF 300,000

- Situation: Fast-growing start-up, low capitalization but excellent profitability

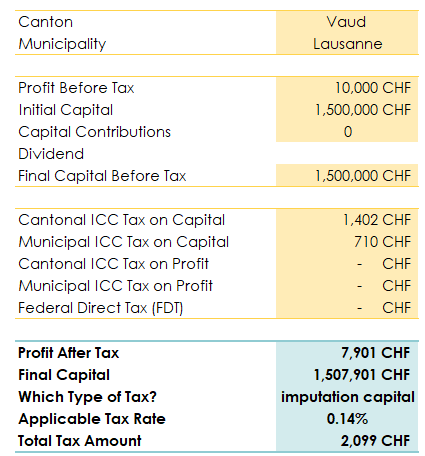

Example 2: Same Company in a Different Phase

- Equity: CHF 1,500,000 (accumulated reserves)

- Profit before tax: only CHF 10,000

- Situation: Mature company with significant reserves but slowed activity

Here’s how our calculations look for these two typical scenarios:

In Example 1, the tax that dominates is clearly the profit tax, with an effective rate of 16.28%. If you apply 16.283% to the CHF 257,991 profit after tax, you get CHF 42,009 exactly.

In Example 2, the opposite occurs: the calculated capital tax exceeds the profit tax. Consequently, a rate of 0.14% will apply to our equity of CHF 1,500,000.

If I were to give you one key figure to remember for your tax simulations, it’s this: as long as your company is based in the canton of Vaud and equity does not exceed roughly 100 times your annual profit, you will almost exclusively pay profit tax.

In the next section, we will explain how tax rates are calculated in the canton of Vaud, so you can apply these principles to your specific situation.

Profit tax rates in the Canton of Vaud

Excellent question! It’s not uncommon to read in the economic press or hear at conferences that “in Switzerland, the corporate tax rate is around 15%”… a figure that is certainly appealing in its simplicity, a nice round number, perhaps a little too perfect in its apparent simplicity.

Let me tell you straight away: this so-called 15% is not entirely accurate! It is acceptable as a rough approximation for general discussions, but it is not precise enough for rigorous tax management. And we, like you I imagine, prefer things that are accurate, precise, and verifiable!

To calculate the exact total profit tax for your Vaud-based company, you need to sum up three distinct components:

- Cantonal profit tax: identical across the entire canton of Vaud

- Municipal profit tax: varies depending on your municipality

- Federal direct tax: uniform throughout Switzerland

This three-tier structure perfectly reflects Swiss federalism, allowing flexibility in local tax policy while maintaining a common national base.

Step 1 – Cantonal and Municipal taxes in Vaud

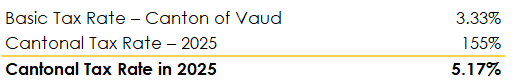

In the canton of Vaud, the cantonal tax operates through a particularly elegant two-step mechanism:

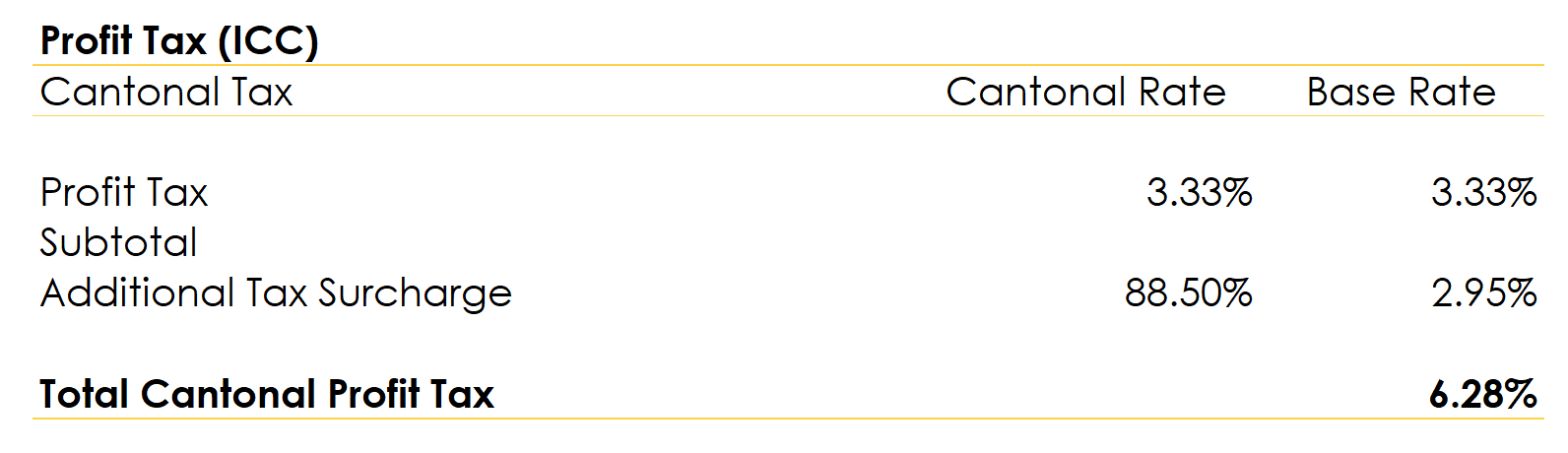

- First component: The Vaud legislator has set a basic tax rate of 3.33% on corporate profits (precisely detailed in Article 75 of the Vaud Cantonal Direct Tax Law).

- Second component: This basic rate is then multiplied by the “cantonal coefficient” voted each year by the Grand Council of Vaud. For the 2025 fiscal year, this coefficient has been set at 155%.

By multiplying the two (3.33% × 1.55), we obtain an effective cantonal tax rate of 5.16%, which applies uniformly across the canton of Vaud, from Nyon to Aigle, and from Lausanne to Yverdon.

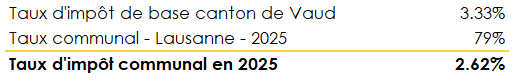

Next, we move to the municipal level, which uses a very similar calculation method but with significant geographical variability.

The principle: Take the same basic tax rate of 3.33% and apply it to the municipal coefficient, which—as you may have guessed—varies considerably from one Vaud municipality to another.

The range of municipal coefficients is quite broad:

- Minimum: 46% for the municipality of Éclépens (the most fiscally attractive)

- Maximum: 82% for Treytorrens-Payerne (the least competitive)

For Vaud’s economic capital, the municipal coefficient is set at 79% for 2025. To find the coefficient for your specific municipality, you can consult the official schedule on the Vaud Cantonal Tax Administration website.

In conclusion, for our Lausanne example, the combined cantonal and municipal rate is simply the sum of the two components:

Lausanne Cantonal & Municipal Tax Rate = 5.16% + 2.62% = 7.78%

Step 2 – Federal Direct Tax

We’ve now covered a good portion of the fiscal journey, and fortunately, this final step is fairly straightforward!

The federal direct tax on corporate profits has the advantage of being fixed and uniform: it does not depend on your canton, your municipality, your altitude, or even the view from your office! For the 2025 fiscal year, this federal rate is set at 8.5%. This rate is determined by the Swiss Confederation and applies identically whether a company is based in Geneva, Zurich, Lugano, or the smallest village in Graubünden.

All that remains is to add these three layers of taxes to obtain the total profit tax rate for your company for the 2025 fiscal year:

And like a fiscal magic trick, it’s exactly the 16.28% rate we applied in our previous examples!

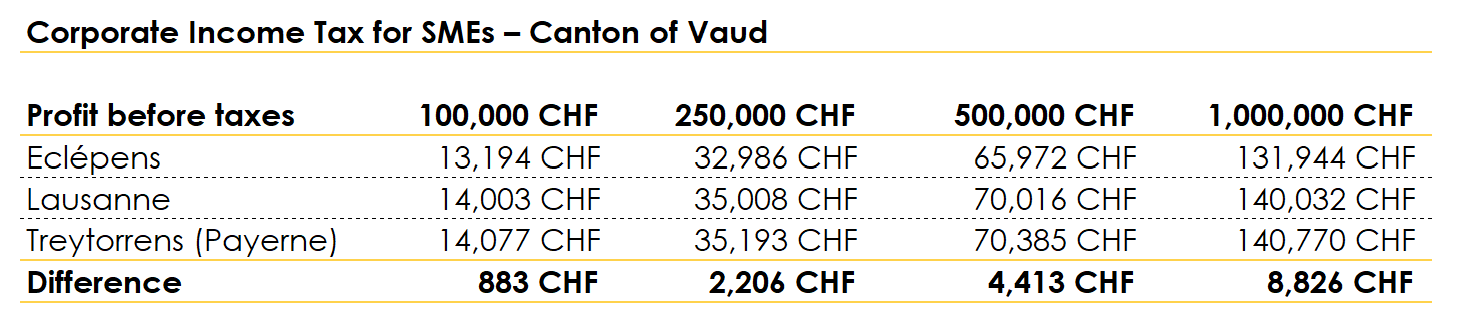

Profit Tax – How does your municipality impact your tax burden?

I could have left it here, claiming my educational duty fulfilled, but I want to help you better understand the concrete impact your municipality can have on your company’s taxation. In other words, whether it could be financially relevant to relocate your headquarters.

To illustrate the stakes clearly, let’s take a taxable profit of CHF 1,000,000 as a reference.

Striking Conclusion: Between the most attractive municipality (Éclépens) and the least competitive (Treytorrens), the difference amounts to CHF 12,000 annually, nearly 10% more in taxes!

This difference may seem modest in percentage terms, but over the lifetime of a company, it represents a significant sum that deserves careful consideration when choosing your company’s location.

Corporate capital tax in the Canton of Vaud

I sincerely recommend reading this section only if you find yourself in one of these specific situations:

- Your company has a very substantial capital (several million francs).

- Your annual profits are close to CHF 0.

- You are in a transitional or restructuring phase, with significant reserves but temporarily reduced activity.

In practice, very few of our clients face a situation where capital tax represents a significant fiscal concern in their planning. As established earlier, as long as the ratio between your equity and your profit remains below 100, this section will remain purely theoretical for your business.

That said, let’s revisit and expand our characteristic example of a Vaud-based company in this particular situation:

- Equity: CHF 1,500,000 (accumulated reserves over the years)

- Annual profit: only CHF 10,000 (slowed activity or transitional phase)

In this specific case, we can mathematically confirm that the capital tax will be significantly higher than the tax calculated on the meager profit. We must therefore assume that only the capital will determine the final tax amount due for this company.

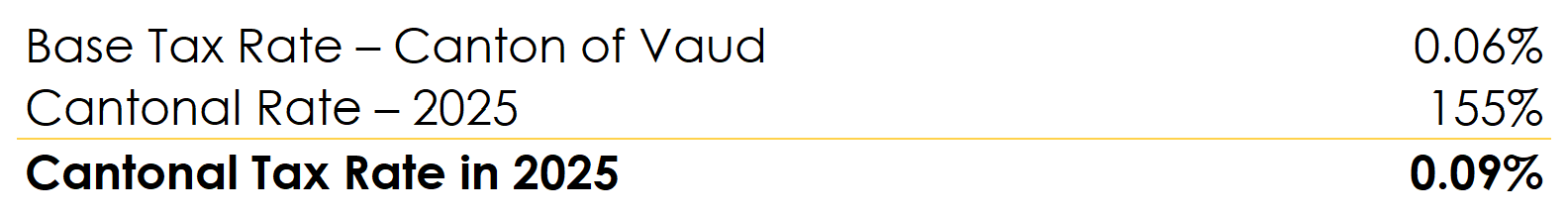

Step 1 – Cantonal and Municipal capital taxes

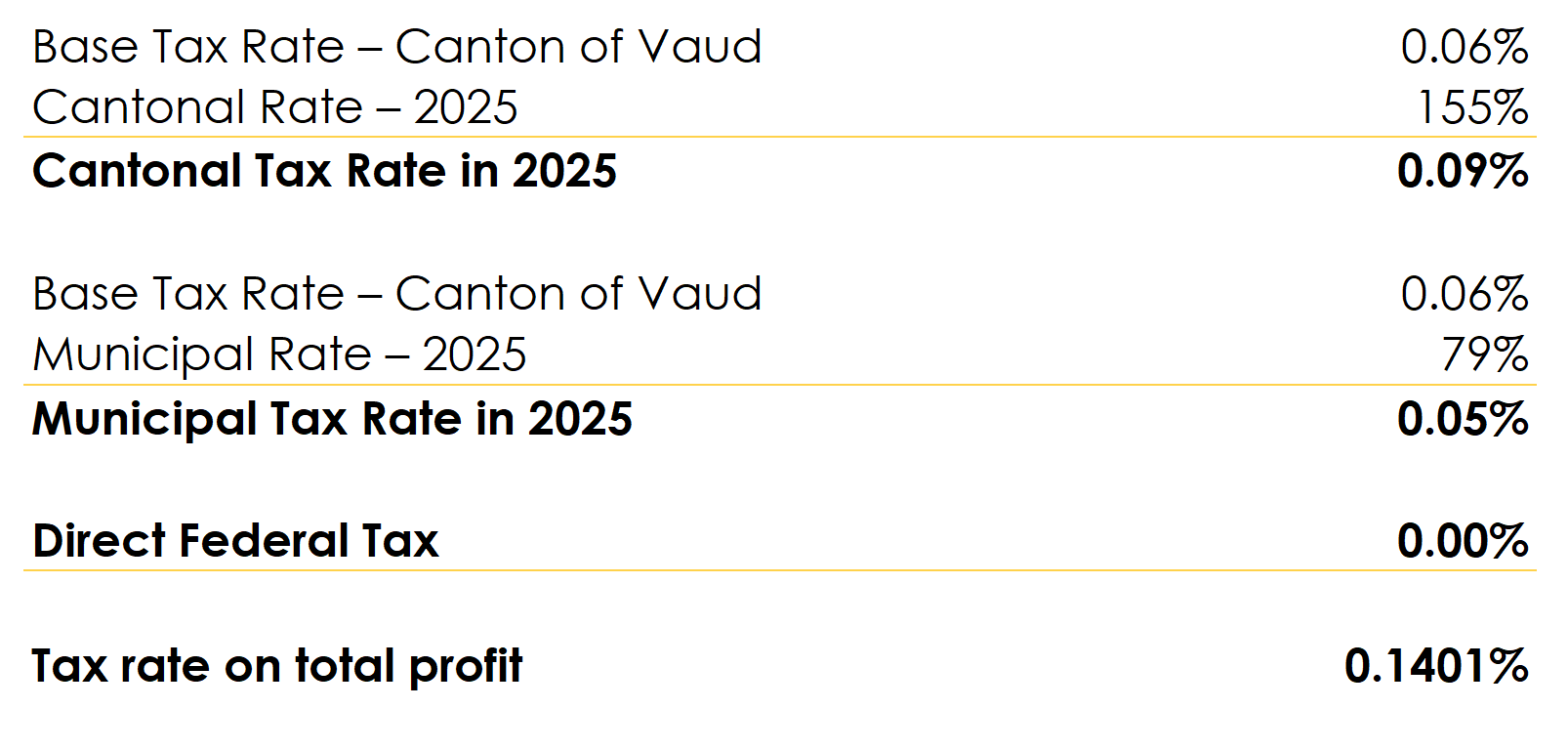

The calculation follows a principle remarkably similar to the one we explored for profit tax, but with rates specifically adapted to capital. The Canton of Vaud applies the same systemic logic as for profits:

- Component 1: The Vaud legislature has set a basic capital tax rate of 0.06% (according to Article 76 of the Vaud Cantonal Direct Tax Law).

- Component 2: This base rate is multiplied by the cantonal coefficient of 155% (the same as used for profit taxes).

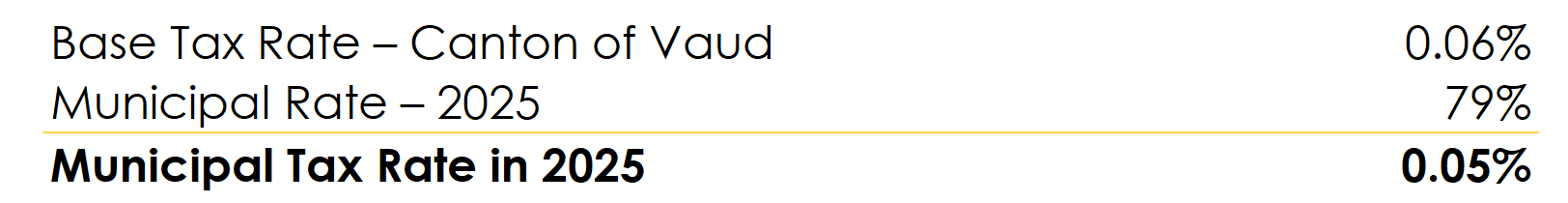

In perfect consistency, the municipality applies exactly the same calculation method: The principle: Take the 0.06% base tax rate and apply the municipal coefficient specific to each locality.

Important to note: The municipal coefficient used for capital tax is exactly the same as the one applied for profit tax! For Lausanne, this coefficient remains 79%.

Here’s great news for companies subject to capital tax: the Swiss Confederation has generously chosen not to tax corporate capital!

This major policy decision significantly simplifies calculations and reduces the overall tax burden. The federal capital tax rate is therefore 0%, unlike the 8.5% applied to profits. The final result is simply the sum of the cantonal and municipal rates, which should then be applied to your net equity:

Using the concrete figures from our case study, we now need to apply our famous formula: Capital after tax = Capital before tax ÷ (1 + tax rate): CHF 1,500,000 ÷ (1 + 0.001401) = CHF 1,500,000 ÷ 1.001401 = CHF 1,497,901.

Fiscal result: The annual capital tax amounts to CHF 2,099.

There you have it, dear readers from Vaud! I sincerely believe you now have a solid understanding of your cantonal taxation after this first read. You master the two main components of corporate taxation in Vaud and can anticipate your tax liabilities with remarkable precision.

I’ll now turn, with a mix of enthusiasm and mild despair, to the equally detailed explanations for the Canton of Geneva. Unfortunately for me (and perhaps for you!), our friends in Geneva have decided to make things considerably more complex…

Before leaving you in this fiscal jungle, don’t forget to check out, at the end of the article, what FBKConseils can concretely offer you and your business. And if any points remain unclear or specific questions arise, consider booking your free 20-minute initial consultation.

Corporate taxes in Geneva: Welcome to complexity!

Honestly, I prefer to be completely transparent from the start: the Canton of Geneva, for both individuals and companies, has developed a particularly intricate tax calculation system. Our neighbors on the Lake Geneva shore have deliberately chosen to maintain their own historical tax logic, but have gradually made it more complex over the decades.

The result? A sophisticated entanglement between capital tax and profit tax, with specifically Genevan concepts such as “basic taxes”, “additional centimes”, “multiplicative coefficients”, and even “precarity funds”… This unique tax architecture makes my mission to provide a simple and effective method to calculate your taxes… let’s say… particularly challenging!

Fortunately, there is good news in this complex fiscal landscape: there’s a very strong chance that your Geneva-based company will only have to deal with profit tax!

Indeed, our analyses show that capital tax only comes into play, on average, when a company’s capital is approximately 14 times higher than its annual profits (compared to 100 times in the Canton of Vaud). This difference is due to the distinct rates and calculation mechanisms between the two cantons.

Faced with this Geneva-specific complexity, here is my methodological proposal:

- Clearly detail the calculation of profit tax (which affects 95% of companies)

- Outline the general principles of capital tax for exceptional cases

- Provide a precise but tedious calculation method

- Advise seeking professional help for complex situations involving significant equity (whether from us or another specialized firm)

This approach allows you to master the essentials while keeping the subtleties of the Geneva tax system in mind.

Profit tax – The daily reality for Geneva companies

In this first detailed section, we will assume a realistic scenario where your company has a “modest capital” and higher revenues, which indeed corresponds to the profile of 90% of our active clients. For our running example, let’s imagine that FBKConseils is not a fiduciary based in Lausanne, but has strategically decided to relocate its headquarters to Geneva. For fiscal year 2025, our accounts would show:

- Profit before tax: CHF 500,000

- Share capital before tax: CHF 20,000

- Location: Geneva, municipality of Carouge

The first crucial step in the Geneva system is to calculate precisely the overall tax rate to apply to your profits. This determination depends directly and entirely on your municipality of registration.

Step 1: Cantonal basic tax rate

This first step has at least one advantage: it is the same regardless of the municipality where your company is based in the canton of Geneva! The basic mechanism is similar to that of the canton of Vaud, but with Geneva-specific terminology and percentages:

- Component 1: The cantonal basic tax rate is 3.33%, just like in Vaud (in accordance with Article 92 of the Geneva Law on Corporate Taxation).

- Component 2: To this base rate, the Genevans add what they call the “cantonal additional centimes”, which are fortunately fixed across the canton at 88.5%.

In summary, you need to add the base 3.33% to 88.5% of that same 3.33%, resulting in a total tax rate of 6.28% for the Canton of Geneva. That concludes the cantonal part. Take a deep breath, because now we move on to the communal part… and this is where things get tricky!

Step 2: The basic communal tax rate

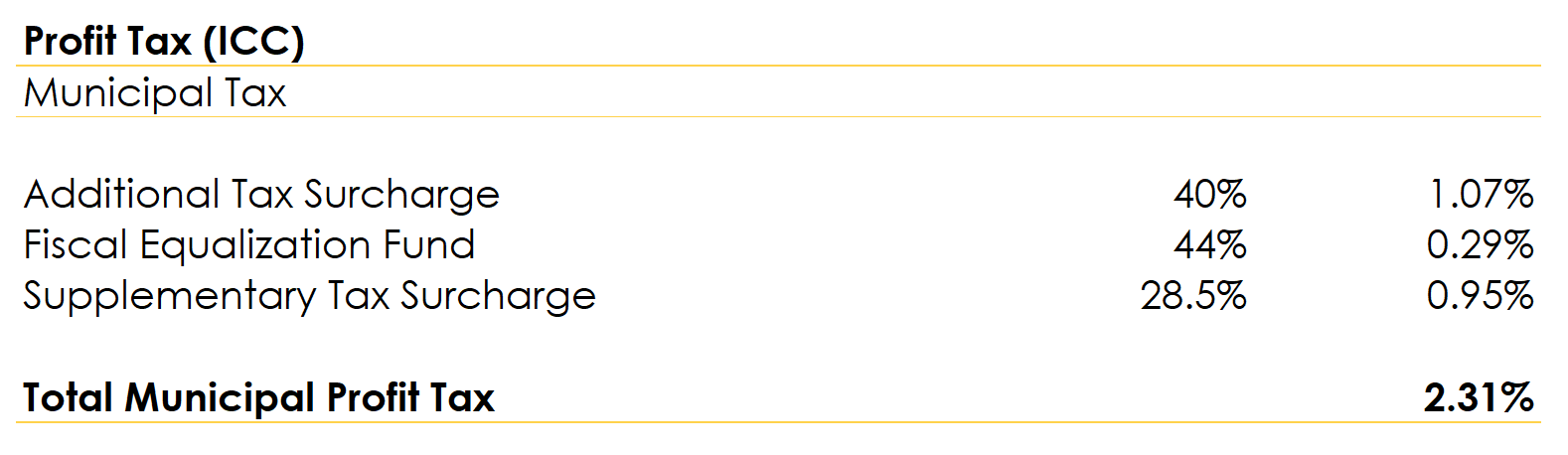

Your municipality will now set several different rates, each of which will apply to a different fraction of the base tax rate. I’ll try to explain this Byzantine logic, but I know full well that what follows may not make much sense at first glance. My pragmatic suggestion: take it as it comes, with patience and resignation. With numerical examples, things will probably become a bit clearer.

To illustrate this complex mechanism, let’s use the rates for the municipality of Carouge (chosen for its representativeness): the Canton of Geneva has set the communal rate at 40% for Carouge. But be careful: for this communal rate, you should only consider 80% of this amount in this first step, as the remaining 20% will mysteriously come into play later in the calculation.

The calculation: Base rate (3.33%) × Communal rate (40%) × Applicable fraction (80%), Result: 3.33% × 40% × 20% = 1.07%

Now the “missing” 20% from the previous step comes into play! In this “equalization fund” step, you need to use the rate in effect for 2025, which is 44%. This rate is always multiplied by the base rate of 3.33%, but this time, you only consider the remaining 20% (instead of the 80% from the previous step).

Calculation: Equalization rate (44%) × Base rate (3.33%) × Applicable fraction (20%)

Result: 44% × 3.33% × 20% = 0.29%

The final step in this fiscal journey: the communal additional centimes, which amount to 28.5% for Carouge. The same arithmetic process applies: take 28.5% of the 3.33% base rate.

Calculation: Communal additional centimes (28.5%) × Base rate (3.33%)

Result: 28.5% × 3.33% = 0.95%

All that remains is to, painfully and without fully understanding all the “whys”, add these three sub-steps together to get a communal tax rate of 2.31%.

Important note: As everywhere else in Switzerland, you must also add the federal direct tax, which is always 8.5%, to this cantonal and communal tax.

If you agree, let’s stop here with all these convoluted steps, because I’m not sure this detailed dissection really helps you in your day-to-day management. This administrative complexity is more fiscal folklore than genuinely useful guidance!

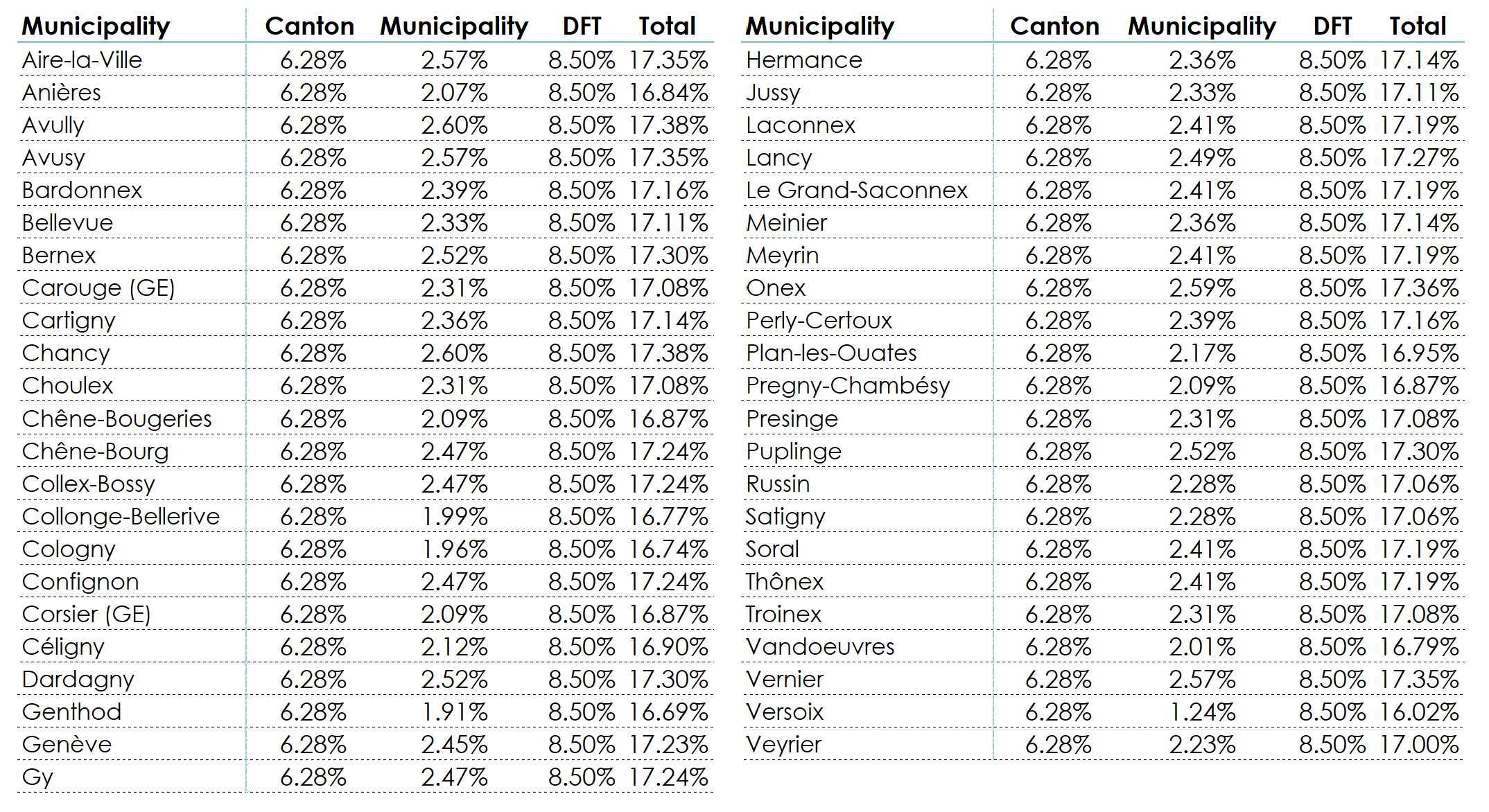

Instead, I propose a far more practical approach: I’ll give you the finalized tax rates for each Geneva commune, so that you can simply apply the formulas we discussed earlier in the theoretical part of this article.

Corporate profit tax rates by Geneva commune – The Life-Saving table

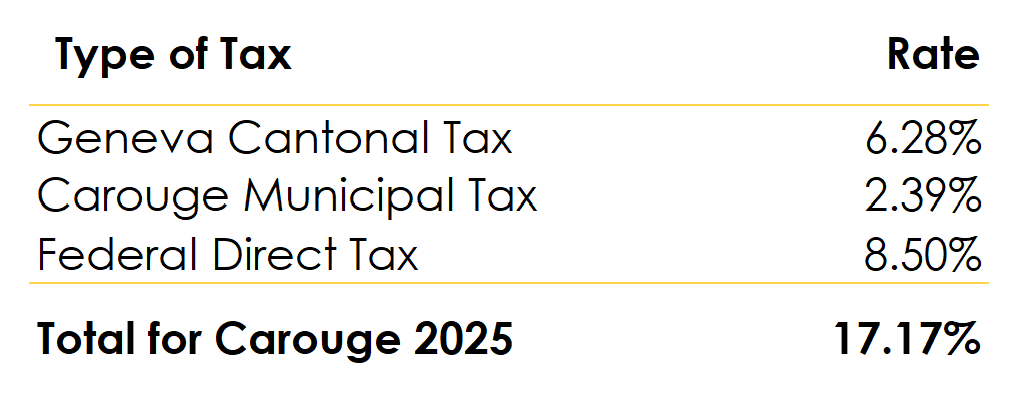

After taking the time to calculate and carefully verify (with a lot of patience!) the effective tax rate for each Geneva commune, here is the summary table that will save you many headaches:

Cool, right? You now have all the tools to calculate your Geneva corporate taxes precisely without getting lost in administrative mazes!

To anchor these theoretical concepts in real entrepreneurial practice, let’s take our medical company example used for Vaud, but imagine it now as an LLC (Sàrl) domiciled in Carouge.

- Domicile: Carouge (Canton of Geneva)

- Pre-tax profit: CHF 300,000

- Equity: CHF 20,000 (initial contributions only)

Applying the total tax rate determined for Carouge (17.08% according to our table), the precise calculation is:

Profit after tax = Pre-tax profit ÷ (1 + tax rate)

CHF 300,000 ÷ (1 + 17.08%) = CHF 300,000 ÷ 1.1708 = CHF 256,235

Tax breakdown:

- Profit after tax: CHF 256,235

- Total tax due: CHF 300,000 – CHF 256,235 = CHF 43,764

To confirm accuracy, the tax indeed represents 17.08% of the post-tax profit:

CHF 43,764 ÷ CHF 256,235 = 17.08%

The key point to always remember is that your capital should not exceed roughly 14 times your profit (we previously used 10x as a rough example, but the precise rule is 14x).

- If this ratio is respected, you remain in the simple case above, and only corporate profit tax applies.

- If this ratio is exceeded, you will unfortunately need to calculate a complex mix of profit tax and capital tax, which requires either patience or the help of professionals!

This is convenient, as I am about to close this article by giving you some practical and important information about the Geneva capital tax!

Capital tax for Geneva companies

If I struggled quite a bit explaining the mechanisms of corporate profit tax in Geneva, I must warn you upfront: I will likely struggle even more with capital tax! The administrative complexity here sometimes borders on the absurd.

My practical advice: the simplest approach, if I were in your shoes, would be to read these few lines to understand the general principles, and then contact us for a free discussion to get personalized answers to any specific questions that remain unanswered.

But since we must proceed, let’s go through the exercise. Let’s take a concrete example where, unfortunately for simplicity, your capital is about 20 times higher than your profit. This is a typical case for a new medical practice that received a significant capital injection at the start.

- Pre-tax profit (first year): CHF 50,000

- Initial capital contributed: CHF 1,000,000

- Domicile: Geneva City

- Company age: Less than 3 years (an important detail for what follows!)

The first thing to understand is that when a company earns a profit, that profit is mechanically added to the initial capital to form the total equity.

In our example, if the company earned CHF 50,000, the taxable capital is no longer CHF 1,000,000, but approximately CHF 1,050,000. Our calculation basis is therefore:

- Pre-tax profit: CHF 50,000

- Total capital before tax: CHF 1,050,000

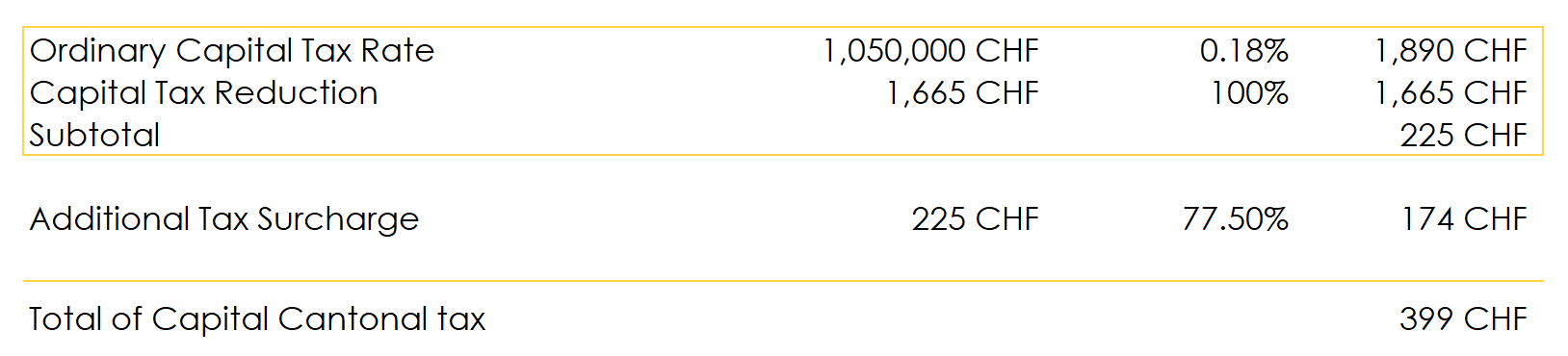

Geneva’s capital tax starts with a fixed rate applicable to the entire canton, set by Article 108 of the Geneva Corporate Tax Law, which for 2025 is 0.18%. The basic calculation is straightforward: multiply this rate by your taxable capital.

Here: 1,050,000 × 0.0018 = CHF 1,890

Here’s where Geneva’s logic gets sophisticated! Once you calculate the basic capital tax, you must subtract a certain amount that is considered already “accounted for” by the profit tax. This mechanism prevents double taxation and coordinates the two types of tax. The amount to subtract is the 3.33% base profit tax rate (as seen earlier) multiplied by the taxable profit.

In our example, the basic capital tax is indeed higher than the basic profit tax. By subtracting the two amounts, the remaining capital tax balance is CHF 225, which will serve as the base for the final calculation.

To obtain the total cantonal tax, you must now, as always in Geneva, account for the famous “additional centimes”. But to make it more “fun,” these are not the same as for the profit tax.

The tax surprise: These additional centimes are completely waived for companies under 3 years old, according to Article 289, paragraph 2 of the Law on Public Contributions.

- Companies under 3 years old: 0% (full exemption)

- Companies 3 years and older: 77.5%

In our example, since the company is older than 3 years, the additional centimes amount to 77.5%.

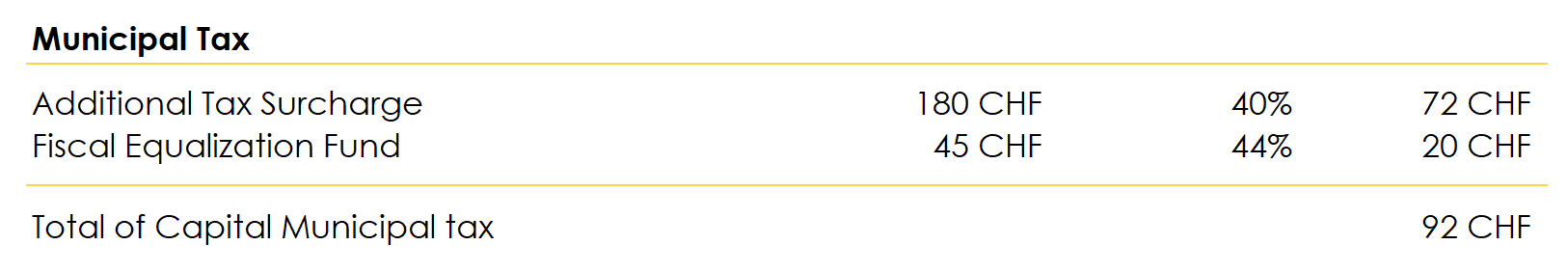

Surprisingly enough, we now have to apply the exact same convoluted logic used for the municipal profit tax, with its mysterious 80% and 20%! The principle is as follows: 80% of the cantonal tax subtotal is multiplied by the municipal additional centimes, while the remaining 20% is multiplied by the equalization fund (fortunately fixed across Geneva at 44%). For the city of Geneva, the municipal additional centimes on capital amount to 40%.

Final step of this fiscal marathon: it’s simply adding the cantonal and municipal taxes to determine the total capital tax for your company: CHF 399 + 92 = CHF 491.

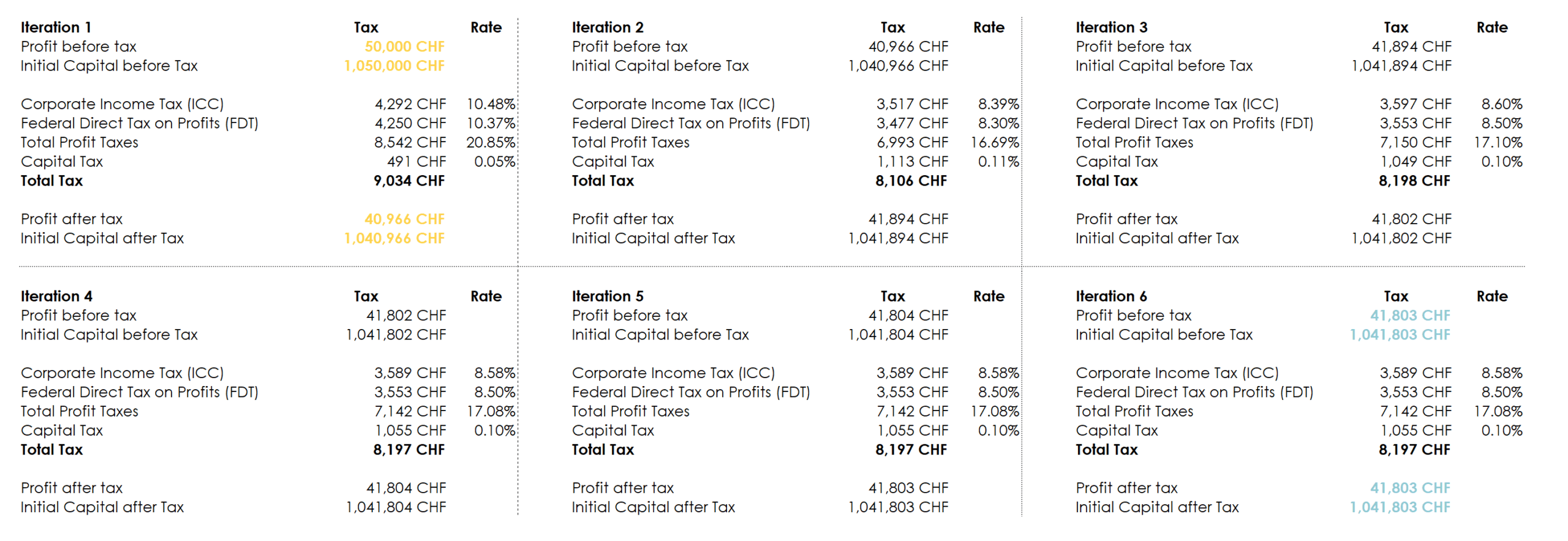

The 6 necessary iterations – the real challenge of Geneva tax calculations

Throughout this detailed example, we used concrete figures to illustrate the mechanisms, but taxes are primarily a matter of rates. And the major problem here… is exactly the same as we encountered at the beginning of this article! If you naïvely start from your pre-tax profit and capital and “blindly” apply the official tax rates, you will systematically overestimate your tax burden. This error arises because taxes constitute a deductible expense that simultaneously:

- Reduces your taxable profit (impact on profit tax)

- Reduces your taxable capital (impact on capital tax)

Unfortunately, the Canton of Geneva has created tax situations where both types of taxes coexist and influence each other. This complex interaction makes providing a simple calculation rule… let’s say… particularly challenging! And at the time of writing, I must honestly admit that I haven’t yet found a perfect mathematical solution to offer.

The sophistication of the Geneva system creates a multi-variable equation where the variables influence each other, requiring an iterative approach. The only rigorously valid method I’ve identified is to start from the pre-tax profit and capital amounts, then reiterate the calculation several times until you obtain a final tax rate that precisely matches the legal rates in effect.

Here is how to calculate the exact tax burden when both types of taxes coexist:

The goal of the exercise is actually quite simple to explain but very tedious to perform manually… Here’s the rigorous method: You start with the pre-tax amounts of profit and capital and calculate the taxes as if they were the final amounts. Then, in each subsequent iteration, subtract the calculated taxes from the initial profit and capital to start again with amounts that already account for the estimated tax burden.

Convergence objective: Repeat this process as many times as necessary until you reach a perfect equilibrium. You know your calculation is correct when you reach this equilibrium:

- The pre-tax profit in your iteration matches the post-tax profit calculated

- The pre-tax capital in your iteration matches the post-tax capital calculated

Only once these perfect equivalences are achieved can you confidently say that the tax burden has been correctly and rigorously calculated.

How FBKConseils can help you?

At FBKConseils, whether for personal or professional matters, we offer a free 20-minute consultation to answer any lingering questions. And at this point in the article, I’m sure there are still a few!

This first meeting allows us to understand your specific situation and guide you toward the solutions best suited to your needs.

Accounting and tax management for your business

Beyond writing articles, we also provide, like any fiduciary firm, a full accounting and tax service for businesses. We offer several packages that can range from:

- Full delegation: accounting, taxation, and social insurance management

- Personalized training: enabling you to take control of your accounting

- Review and validation: checking your existing work

- À la carte service: intervention according to your specific needs

Strategic business advice

Sometimes, the challenge isn’t execution but a broader understanding of your situation. If you have enough questions—whether about yourself, your employees, or your business—we offer unlimited-time consultations to:

- Perform simulations together

- Answer theoretical questions

- Brainstorm your fiscal and wealth situation

Business creation

In addition to traditional services, we assist you with all steps related to starting your business:

- Developing a business plan

- Economic and tax simulations

- Choosing the optimal legal structure

- Completing all steps needed to turn an idea into a registered company