Written by Yanis Kharchafi

Written by Yanis KharchafiEntrepreneurship: Becoming freelancer or starting your own company?

Introduction

As the years go by, does the desire to be your own boss and work for yourself keep growing? Let me guess—you’ve done your research and reached a simple conclusion: you have two options. Either you start as a sole proprietor and work as a self-employed individual, or you gather capital and aim bigger by launching your own company.

Am I right? Believe me, if I’m writing these lines, it’s because this question comes up time and time again. Whether you’re a doctor, a consultant, or planning to open a retail business, this choice is often misunderstood. Yet, it’s the very first decision you’ll need to make.

Hopefully, by the end of this article, all your doubts will be gone, and you’ll be ready to embark on your new adventure!

The line-up:

What’s the difference between being self-employed and being employed by your own company?

It’s not uncommon for our clients to have preconceived—and often inaccurate—notions about the self-employed status compared to starting a company. In Switzerland, this concept is still widely misunderstood. For example, did you know that many restaurants employing dozens of people still operate under a self-employed status, while a solo fitness coach can perfectly well start their own company? In Switzerland, nearly all professions can be carried out either as a self-employed individual or by creating a legal entity. Understanding the legal differences between these two statuses is therefore absolutely essential.

Option 1: Becoming self-employed in Switzerland

To put it simply, a self-employed person, as the name suggests, is an individual who has decided (or sometimes had no choice but) to carry out a profit-making activity. In other words, they do what it takes to earn more than they spend while practicing their profession. They operate without a legal structure above them and are responsible for almost everything: finding clients, delivering the services or products sold, invoicing, tracking payments, and, of course, complying with legal requirements—whether fiscal, administrative, or otherwise.

Does this mean a self-employed person must work alone? Not necessarily! A self-employed individual can collaborate with others, whether businesses or fellow self-employed professionals. They can even hire as much staff as needed to complete the work entrusted to them.

Taxation for the self-employed in Switzerland

We’ve already covered this topic in detail in a dedicated article on self-employed taxation, but here’s a quick summary. A self-employed person maintains accounting records where they report all their income and deduct all expenses. The difference between the two gives the annual profit of the business. This profit is what gets taxed. How? Quite simply, just like a salary—it follows the same tax brackets and calculations!

What you need to understand here is that the more you earn, the higher your tax rate will be—and trust me, it climbs fast!

For more details on tax rates in different Swiss cantons, check out our dedicated articles:

A self-employed person can never choose whether or not to pay themselves a specific salary. Whatever they earn from their activity, after deducting all allowable expenses, will simply be taxed — end of story!

How to become self-employed?

Just like taxation, we’ve previously detailed the full process of becoming officially recognized as self-employed.

A key point that might not have been emphasized enough in that article is that several administrative bodies will review your independent activity:

- Social Security Administration (AVS): This entity will assess your business and issue an official certificate confirming your self-employed status. To gain this recognition, you simply need to prove the legitimacy of your business (showing existing clients, prospects, expenses, income, etc.).

- Tax Authorities: Even if AVS does not fully validate your business as a legitimate independent activity, the tax authorities won’t hesitate to tax any income they deem as profit-driven. For example, if you sell a watch you originally bought for CHF 1,000 at a price of CHF 5,000, you won’t be taxed because the purchase wasn’t made with the intention of making a profit. However, if you buy 10 watches every month and resell them for a nice profit, there’s little chance you won’t be considered self-employed.

In short, as soon as you engage in any activity with the goal of making a profit, taxation applies—no debate. If AVS hasn’t recognized your status yet because you haven’t initiated the process, don’t worry. The tax authorities will report your income to the first pillar (AVS), and you’ll receive a notice to regularize your situation.

How much does it cost to start a sole proprietorship?

Let’s get straight to the point—starting a sole proprietorship itself costs nothing! Absolutely nothing. If you handle all the steps with the various administrative bodies yourself, there won’t be any fees to pay. However, do keep in mind that once your income exceeds CHF 100,000, you’ll be required to register with the commercial registry, which will incur a small registration fee, usually around CHF 150.

On the other hand, if you’d prefer not to handle the paperwork yourself and want to entrust it to a professional, like us, the cost will be based on the time spent on your file. But in this first option, there’s no need for a notary or initial capital.

Option 2: Start a company and be employed by your own business?

In this case, everything changes. Creating a company essentially means you’ll separate your personal responsibilities from those of your business. You’ll become two distinct entities at all levels. What you need to understand is that, in addition to yourself, you’ll now have another “person” to manage—the company. As an individual, you’re the physical person, while the company is considered a moral entity.

In Switzerland, there are many types of companies, but the two most well-known for running a commercial activity are the SA (Société Anonyme) and the SARL (Société à Responsabilité Limitée).

How to choose between a limited liability company (SARL) and a public limited company (SA)?

To keep it simple, a public limited company (SA) is very similar to a limited liability company (SARL), but there are some key differences:

Anonymity

In the name “société anonyme,” the word “anonyme” indicates that no one (or almost no one) is supposed to know who owns the company. In the commercial register, only the names of the directors and the audit body appear — not the owners of the company. On the other hand, in an SARL, all the partners are named, and their identities are publicly known.

Initial capital

When starting the company, funds are needed to give your business a chance to run and pay the first bills. For an SA, a capital of CHF 100,000 is generally required, although in practice, only CHF 50,000 is mandatory. In contrast, for an SARL, the initial capital is much lower: CHF 20,000.

Corporate governance (who makes the decisions)

In an SARL, it’s generally the partners holding shares in the company who make all the decisions. However, in an SA, the owners must appoint a board of directors, which then designates the management board. This may all sound complicated, but don’t worry, you could hold pretty much any role, and in practice, the difference may not be that noticeable.

What are the steps to start a business in Switzerland?

Once again, there are many misconceptions… How many times have we heard our clients say that starting a business is tedious, long, and expensive? Well, not really. Starting a company becomes complicated when the idea behind it isn’t perfectly clear, but once you have your business defined, here are the steps:

Choose a name for your business

Every company needs a name that will appear on all your communications and interactions with the parties involved in your new business.

An address

Whether you rent office space or not, a company in Switzerland needs a correspondence address. This could be your home (in Switzerland), your office, or even your fiduciary’s office.

Define who will be involved in the project

Depending on who is contributing what, and who has done what in the company, it’s important to define who will own the company and who will manage its operations. Roles should be clearly defined.

Draft the articles of association

A company must have a purpose. You will need to define what your business will do in a fairly precise way, while keeping it broad enough to allow for expansion as your business grows over time. In any case, the notary handling your file will take the time to verify and validate them.

Open a holding account

Once the name, address, roles, and articles are defined, you can contact your bank to request the opening of a holding account to receive the initial capital.

Create the company

Once the funds have been transferred, you will need to wait for the commercial register to process your request and validate the account opening.

In terms of timelines, you can expect it to take between 1 and 2 months to have a registered and operational business.

These steps lay the foundation for the company, but once registered, you’ll have additional steps to complete in order to start operating, such as registering for social security, VAT, etc.

How much does it cost to start a business in Switzerland?

It’s not uncommon to hear that the costs of starting a company are high and may discourage some people. Notary fees, registration fees, consulting costs, etc., can seem intimidating. However, in the end, the only expensive cost is the notary fee because, unfortunately, these steps require a notarial act. But when you know the right people, those fees can be significantly reduced, ranging from CHF 500 to CHF 700 for notary services. On top of that, you will have the registration fees, which are higher than those for sole proprietorships.

But hey, Noé, what about the CHF 20,000, CHF 50,000, or even CHF 100,000 required for the opening? I didn’t forget that! While it’s true that you need to come up with this amount, it’s not considered an expense. Once your company is created, that money will be back in the business bank account.

How does business taxation work in Switzerland?

Unfortunately, I haven’t had time to write further articles on this topic yet, but I promise I’ll get to it soon. In the meantime, here’s a quick summary of the situation.

Companies in Switzerland are taxed on their profits at a fixed rate, regardless of the amount. The corporate income tax rate is around 15% (it may vary slightly depending on the canton). In some cases, a relatively low capital tax may also be payable. The key takeaway is that, regardless of your profits, you’ll need to pay a 15% tax rate on your income (excluding VAT).

Who wins between being an independent contractor and starting your own company?

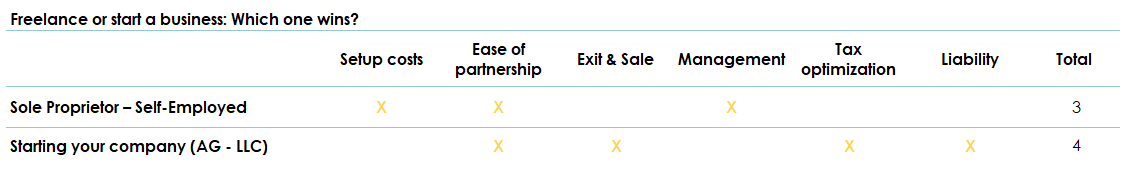

After all these discussions, we’ve probably reached the real point of this article: is it better to start your business as an independent contractor or create your own company and commit to it full-time?

Responsibility

On this point, I’d say that independents lose quite significantly. An independent contractor is always personally responsible without limits for their actions, while by running a company, it is the company itself that holds responsibility.

The cost of creation

As we’ve seen in the previous sections, there is a clear difference, and independents have the upper hand. The fact that no notary is required to set up a sole proprietorship keeps the costs lower. However, the overall cost is not drastically different, ranging between CHF 600 and CHF 1,000, regardless of the type of company you choose to create. This doesn’t include the registration fees for the commercial register or other essential costs to kickstart your business.

Partnership – Being an entrepreneur with others

This is another point that frequently comes up. You might start off thinking you’ll embark on this adventure solo, but quite often, businesses are the result of partnerships between multiple people. So, what should you choose if this is the case for you? It’s a bit more complicated, but in principle, both options are possible:

Freelancers (partnerships)

When several independent contractors decide to work together on a project, this is called a partnership or a general partnership (société en nom collectif). You’ll remain independent but with a shared common goal. You’ll share expenses, revenues, and ultimately, each person will take what is rightfully theirs. A little advice: it’s best to put a contract in place with your partners that clearly outlines each person’s responsibilities and rights. Again, independents enjoy a lot of flexibility, as no formal setup is required aside from reaching an agreement among all partners.

Companies (corporations)

When you create a company, you inevitably end up with shares of the future company. It’s like a big cake, where each owner of the company will have the right to a portion, usually proportional to their contribution, whether it’s at the time of creation or later on. The fact that a company is made up of shares makes transactions between partners easier to handle.

Accounting

This question raises a lot of doubts… Not as much as taxation, which we’ll cover later, but accounting is still a big topic. Is there a difference between the accounting of self-employed individuals and that of companies? Unfortunately, the answer may disappoint you: there is no difference! There is only one type of accounting that is fiscally accepted, regulated by the Swiss Code of Obligations, specifically Articles 957 and following. These articles explain how both legal entities and independent contractors must manage their annual accounts. So forget about phrases like “independents can’t hire employees” or “it’s possible to deduct more expenses as an employee than as an independent contractor” because the legal basis is exactly the same!

However, there is one exception for “small” independents (that’s what the Code of Obligations calls them), who have an annual turnover of less than CHF 500,000 (Article 957.2). These individuals are allowed to keep a simplified record, basically a ledger to track income, expenses, and assets. But ultimately, despite this exception, the main accounting and tax rules remain unchanged.

Conclusion? No accounting difference. Regardless of the option you choose, you will have to adhere to this painful task without being able to benefit from any advantages, whether you go the independent route or opt for setting up a company.

Taxation and tax filings

This is where things could really start to get lengthy, because everything boils down to this last section. Even though the accounting accepted for tax purposes is the same for both independent contractors and employees of their own company, the tax implications in practice will differ drastically.

Where do we start? First, let’s tackle the question of what income is taxed and when.

An independent contractor who generates a profit (which is the goal of any business) will do their best to deduct all possible expenses and minimize their revenue. But the profit that can’t be erased by these expenses will have to be declared every year on their tax return. This profit will be added to all other income. What does this mean? Let’s imagine you made a profit of CHF 100,000, but you only need CHF 60,000 to live. The remaining CHF 40,000 cannot be kept within your individual business but will be subject to tax and eventually end up in your bank account whether you want it or not.

Now, let’s look at you, who decided to create a company generating CHF 100,000 in profit. This time, the situation is different. You can decide the “salary” you want to pay yourself. In other words, you could choose to pay yourself CHF 60,000 and leave the CHF 40,000 in your company. What’s the benefit? The CHF 40,000 will be taxed at a lower rate within the company and won’t be added to your personal income for that year.

In this case, there will be two separate taxes: your personal income tax on the CHF 60,000 salary you paid yourself (just like an independent contractor), but since you get to decide the amount you’re taxed on, and the corporate tax of approximately 15% on the remaining CHF 40,000.

It’s important to note a few other things:

With your company, when you pay yourself a salary, the company must also pay contributions to the AVS (Old Age and Survivors Insurance) and LPP (Occupational Pension Plan), i.e., the first and second pillars of retirement. This adds an additional charge for the company, but since it is a business expense, it is also deductible from taxes.

In practical terms, a lot can be done for tax optimization depending on whether you choose to create a company or become an independent contractor.

Income tax is generally capped at around 40% for higher incomes, which is significantly higher than the company tax rate of around 15%. Therefore, you could choose to pay yourself a small salary just for your needs, so as not to pay too much tax on your personal income, and keep the maximum profit in your company, paying only the 15% corporate tax. This is a possibility, but be cautious: at some point, that money in your company will need to be withdrawn, and the tax will catch up with you at that time.

For tax optimization, another strategy is to pay yourself a relatively stable salary but gradually reduce your activity rate. This way, you’ll have the same salary and taxes but your company’s profit will decrease since you’ll be working less. This allows you to smooth out your income over time, and use the accumulated cash in the company without having to withdraw all the profits at once and possibly face a higher tax rate. This mechanism allows you to smooth out your income, but it doesn’t avoid paying taxes.

In short, a company allows for better management of cash flow and the owner’s tax burden. Why pay yourself a high salary and face high taxes when, in the following years, the business may slow down or you might want to reduce your workload? It’s in those years that the CHF 40,000 you didn’t pay yourself could be paid out, thereby reducing your tax burden.

What about dividends?

Another important aspect to consider with companies is the option to pay yourself a portion of the profits in the form of dividends. This is a complex subject, but in Switzerland, it is possible to distribute profits as dividends (not as salary), which is simply not an option for independent contractors—it doesn’t exist. The advantage of dividends is that the amount paid is not subject to social security contributions (i.e., the first and second pillar), and even better, if you hold a “qualified participation” (i.e., more than 10% of the shares in your company), you can get an additional tax deduction on the dividend paid.

Depending on the canton, you may only need to declare 70% of the dividends you’ve received, effectively ignoring 30% of the amount for tax purposes. This allows you to save even more on the tax burden on your income.

We all want to say, “Wow! I can control my company’s payouts, and I can receive dividends that are not subject to social security contributions, so why bother with anything else?” Unfortunately, as you might suspect, neither the tax authorities nor social security agencies are keen on having all of the profits distributed in this way. The authorities will assess what portion can be paid out as a dividend and which part will need to be reclassified as salary.

In other words, while dividends can be a tax-efficient way to extract profits from a company, the authorities will closely scrutinize your decisions to ensure that you aren’t trying to bypass salary contributions and the correct tax treatments. Thus, a careful balance must be maintained between salary and dividend distributions.

Conclusion: Is it better to create a company or start as a self-employed individual?

Every situation is different, not all businesses carry the same risks, and no entrepreneur has the same financial resources… Honestly, as is almost always the case when it comes to money and your responsibilities, everything depends on you. Nevertheless, if I wrote this article, it is precisely to give you a clear answer and share my point of view.

Without hesitation, I would say that if you have at least CHF 20,000 available and a strong desire to start a business, I would opt for creating a limited liability company (SARL). The setup cost is not exorbitant, the process fairly quick, and it offers almost foolproof protection, both legally and financially. Moreover, not only will you be covered by your company, but you will also have significant flexibility in setting your salary and, if needed, choosing other forms of compensation. In short, a capital company allows for more meticulous management of income and expenses and also makes it possible, in the long term, to sell the business in the form of shares or equity stakes. This is not only fiscally advantageous but also much simpler to implement.

Can you convert a self-employed status to create a company in Switzerland?

Good news: the answer is yes! If you have been self-employed for some time and now wish to convert your activity into an LLC (SARL) or a corporation (SA), it is entirely legal and even relatively simple. However, just because something is feasible doesn’t necessarily mean it is the best solution. Indeed, the main potential obstacles are often administrative or financial. In our opinion, you mainly have two options:

Liquidation of the sole proprietorship followed by company formation

If your activity is still recent, with an almost non-existent balance sheet limited mainly to income and expenses, simply ending your self-employed status while simultaneously starting the process of creating a company is an easy solution to implement. You can thus liquidate your self-employed status to become an employee, but this time within your own company.

With this first method, however, it is crucial to be careful regarding contracts previously signed with your clients. Indeed, they contracted directly with you, engaging your personal liability. For a client, it is reassuring to know that if you fail to meet your commitments, they legally have recourse to your private assets. Therefore, make sure, especially with your main clients, that they agree to modify the original contract and continue the contractual relationship with the new legal entity.

From a tax perspective, nothing very complicated: you close your accounts at the end of the year as usual. If you cease your activity during the year, you will simply have no further entries to record after the termination date. You will then report the accounted items in your tax declaration, and that’s it.

Be careful, however, if you have accumulated assets or contracted debts as a self-employed person. Ending a self-employed activity involving assets and liabilities can lead to significant tax consequences if the liquidation is poorly managed. Caution should be your watchword!

Directly transforming a sole proprietorship into a corporation

Another piece of good news: you can also directly transform your independent activity into a corporation (AG or GmbH) without interrupting your activity or needing to create a new legal entity. On paper, this process is relatively simple, but it necessarily requires the involvement of a notary as well as a certified auditor.

Concretely, you will need to maintain perfectly clear and accurate accounting up to the day of the transformation, then submit your accounts to an auditor who will certify that your activity indeed has the necessary funds for the transformation and that your balance sheet is fairly valued. Once this audit is validated, you will approach a notary who will draft the official deed of transformation. These complete documents will then be submitted to the commercial register, where they will be verified and recorded. A few days to a few weeks after this procedure, your sole proprietorship will officially become an AG or GmbH, depending on your initial choice.

However, be aware that although this process may seem simple when described in a few lines, it can be costly. The more complex your balance sheet, the more time the auditor will need to audit each item in detail. Expect costs between CHF 1,500 and CHF 5,000 for the audit, plus approximately CHF 1,500 to CHF 3,000 for the notary fees to draft the transformation deed.

How FBKConseils can support you?

Introductory meeting

At FBKConseils, we offer all our new clients an initial consultation of about twenty minutes free of charge, which can take place either via videoconference or in person at our offices in Lausanne. This first meeting is the perfect opportunity to complete the information available on our website and answer any questions you may have.

Simulation: becoming self-employed or creating a company

As discussed in this article, choosing between working as a self-employed individual or creating a company has many practical, financial, and tax implications. Many of these consequences can be calculated and anticipated precisely. At FBKConseils, we offer to carry out these simulations with you to facilitate your decision-making process.

Setting up your sole proprietorship and support for becoming self-employed

If your goal is to become self-employed, FBKConseils can assist you at every step of the process, both administratively and technically. With us, you are free to choose exactly which steps you want to handle yourself and which you prefer to delegate.

Company formation

We have all the necessary expertise to effectively advise you and handle the administrative procedures related to the creation of your company, whether it is a GmbH, an AG, or any other legal structure suited to your needs.

Accounting and tax management of your activity

As a recognized fiduciary, our role is not limited to providing strategic advice. We also offer comprehensive support to all entrepreneurs to fully meet their legal obligations: preparation of VAT returns, full accounting management, payroll processing, handling social insurances, issuing salary certificates, as well as tax declaration services for both individuals and companies.

Please feel free to create your own customised quote directly on our website.