Written by Yanis Kharchafi

Written by Yanis KharchafiInvesting in real estate: Understanding the tax implications of your project

Introduction

If you’ve been following our series of articles on investments and taxation, welcome to this new installment dedicated to real estate projects. Very popular in recent years—driven by the sharp decline in mortgage interest rates at the end of 2025 and by property prices that continue to rise—you have probably also considered investing in real estate.

But beware: real estate in Switzerland is an endless source of taxes. It all starts at the time of purchase, then continues with income taxes, wealth tax, property taxes, and goes on all the way through to the sale. And that’s only the tip of the iceberg: depending on whether you buy as a private individual or through a company (real estate company such as a Ltd / LLC), everything can change—not to mention the differences from one canton to another.

In short, real estate in Switzerland can be an excellent investment, but to properly manage the taxation surrounding it, you need to be well prepared. We will therefore try, step by step, to cover these topics by offering for each one:

- a brief theoretical reminder, followed by

- a numerical example.

As always, your personal situation may not exactly match our case studies, but we remain available to answer your questions.

The line-up:

Part 1 — Buying an income-generating property directly (as a private individual)

This first section aims to describe the tax impact of an income-generating property when you invest as a private individual, without any specific legal structure. In this case, you, as a natural person, become the owner of the property and must:

- Declare the rental income received as taxable income,

- Deduct the expenses related to the management and maintenance of the property,

- Report the property’s tax value in your personal tax return,

- And deduct the debt incurred to finance the real estate purchase.

If you have read our previous articles on Swiss taxation, you already know that there are two main types of taxes involved here:

- Income tax: this applies to your salaries, dividends, pensions, annuities, rental income, etc.

- Wealth tax: this applies to your bank accounts, real estate, investments, shareholdings, valuable assets, etc.

It is the combination of these two taxes that ultimately determines, once the year has ended, your total tax burden as a private property owner.

Income tax

If you purchase an income-generating property in your own name, the rents are paid into your private account and taxed as income (in the same way as your salary), according to progressive tax brackets. In other words, high rental income can quickly push you into higher tax rates. Fortunately, you are not taxed on the gross amount: the law allows you to deduct the expenses required to generate that income. In practice, as long as an expense is directly linked to renting out the property and can be justified, it is generally deductible. Typical deductible expenses include:

- Building insurance

- Ongoing maintenance costs (or a lump-sum deduction, depending on the canton)

- Property tax (where it exists at cantonal/communal level)

- Mortgage interest

- Condominium (PPE) charges borne by the owner (the portion not recharged to the tenant)

- Management fees (property manager, letting costs, advertisements, etc.)

At this stage, you therefore arrive at gross rental income minus deductions, which gives you the taxable income generated by the property.

Wealth tax

And as with all assets in Switzerland, in addition to income tax, there is also wealth tax. Yes… Depending on your canton of residence, real estate wealth tax is calculated differently. You often read that the tax value corresponds to 70% of the purchase price, don’t be fooled, that’s only a rough approximation.

In practice, for example:

- In Geneva, the calculation starts from net rental income received, which is then capitalized using a rate that varies depending on the type of property.

- In the canton of Vaud, the tax value is defined as a weighted average between the purchase price and the income value, and is calculated by the land registry, more specifically by the real estate valuation commission.

In short, each canton has its own method for valuing your real estate. And just like with income, this tax value can be reduced by your debts (in particular mortgage debt) to determine your taxable wealth.

Our running example

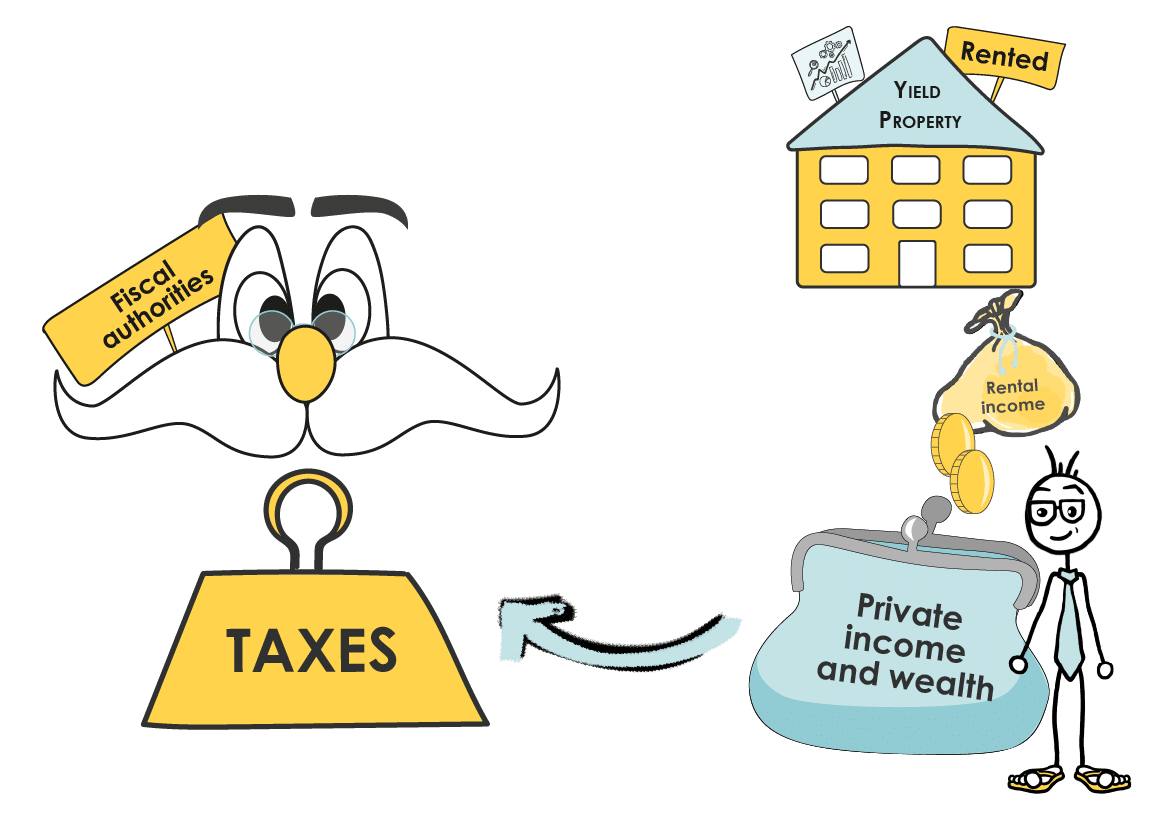

When I read an article, what I really like is a solid theoretical section followed by a numerical example that runs through the entire piece, making it easier to compare the different options in concrete terms. That’s exactly what we’re going to do here. So let’s take my own situation as an example, which can be summarized as follows:

- Taxable income (after all allowable deductions): CHF 100,000

- Bank accounts: CHF 250,000

- Place of residence: Lausanne, in the canton of Vaud

I found a bank willing to finance the purchase of an income-producing property under the following conditions:

- Purchase price: CHF 1,000,000

- Tax valuation: CHF 700,000

- Total loan amount: CHF 750,000

- Annual interest rate: 1%, i.e. CHF 7,500 in interest per year

To simplify the example, we will deliberately leave out acquisition costs (notary fees, transfer taxes, etc.). We will now compare my situation before and after the purchase in order to assess the concrete tax impact of this investment.

This first real estate purchase has a major impact on my tax situation. Before the purchase, my total tax burden (income tax + wealth tax) amounted to CHF 23,300. After acquiring the property, the situation changes: I generate an additional CHF 40,000 in rental income, but my overall tax rate, which now includes these rents on top of my salary, also increases.

In conclusion, out of the CHF 40,000 in rental income received, after deducting all expenses, I still have to subtract around 35% in taxes. The net profit of my investment therefore amounts to CHF 26,233 (40,000 – 13,767). For a property valued at CHF 1,000,000, this corresponds to a net return of approximately 2.6% in my situation.

This solution is perfectly suited to someone who wants to live directly off the rental income generated by the property—in other words, someone who wishes to collect the rents and use them freely. It also has the advantage of simple management: no accounting, no corporate tax return, and no legal structure to maintain.

A small piece of advice: for a first real estate investment, this approach is often the wisest. The administrative steps and constraints are already significant enough at the beginning. Over time and with experience, if you identify a real advantage in doing so, you can always move on to a more complex structure for future acquisitions.

Now let’s move on to the other scenario: purchasing through a company.

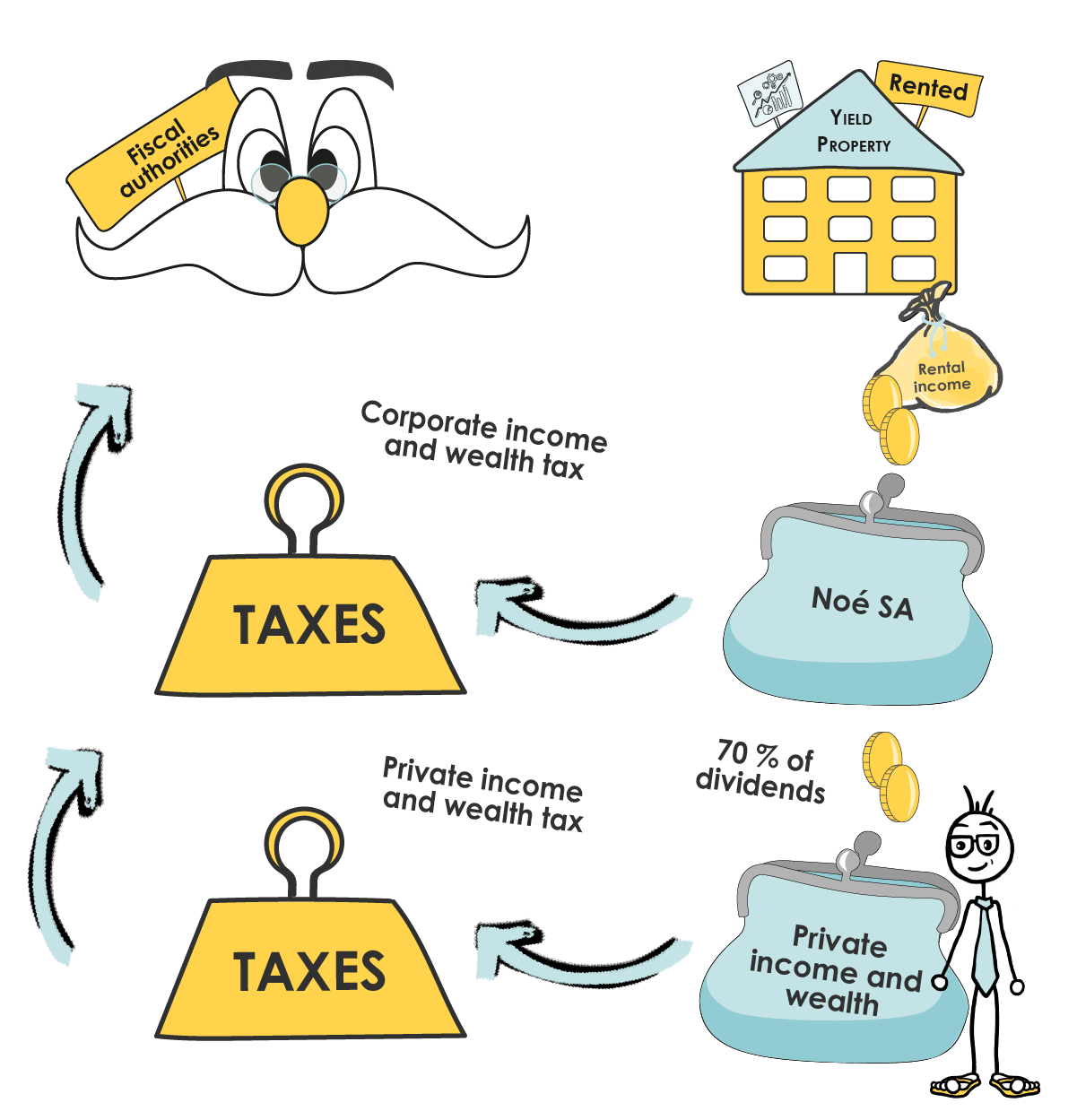

Part 2 – Buying an income-producing property indirectly — setting up a real estate company

The term SCI for the French, or SI for the Swiss, comes up frequently. In Switzerland, this structure is nothing more than a limited company (SA) whose purpose is the management of real estate assets. Given the amounts typically involved, the public limited company (SA) is the legal form most commonly used by individuals to acquire and manage their real estate holdings.

With this second option (indirect purchase), there is no longer just one taxable subject (you), but two: you as a private individual, and the company, which is also liable for corporate income tax and/or capital tax.

Conclusion: to properly understand the overall tax impact of your project, you must add together the private taxation and the company’s taxation.

This type of explanation often remains abstract. So let’s do what we always do: a numerical example from start to finish.

I, Noé LeConseiller, decide on 1 January 2025 to purchase a property via a company (Noé SA) created on the same day.

The property: a small house in the canton of Vaud, made up of two small apartments, for CHF 1,000,000 (we are still ignoring acquisition costs for now). How does this work?

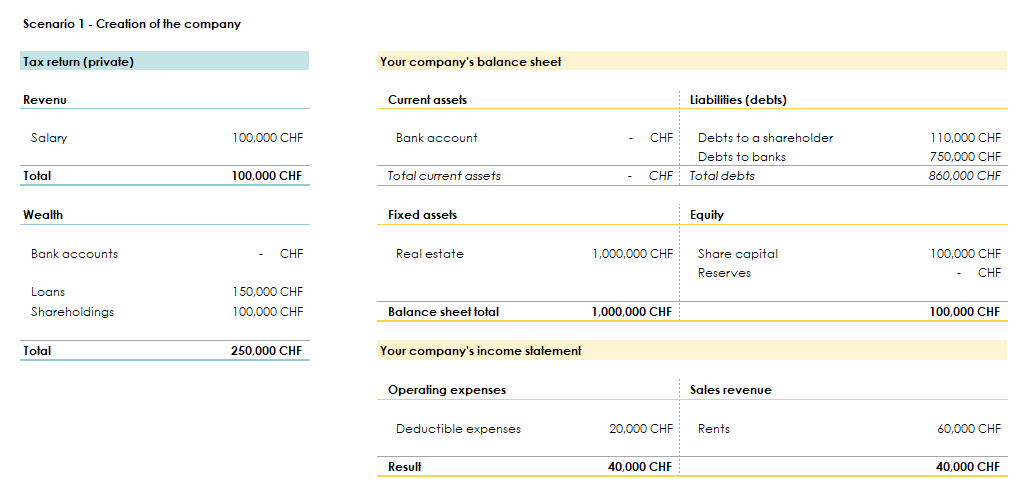

Step 1 — Setting up the company (SA)

In Switzerland, a public limited company (SA) requires CHF 100,000 in share capital. I draw on my savings and contribute CHF 100,000 to Noé SA.

- On the company side: CHF 100,000 is available in the bank account.

- On the private side: I hold CHF 100,000 worth of shares in Noé SA.

Step 2 — Obtaining bank financing

A bank agrees to finance 75% of the purchase price via a mortgage in the name of the company, i.e. CHF 750,000.

Step 3 — Covering the balance

There is CHF 150,000 missing (1,000,000 – 750,000 – 100,000) to finance the property. I contribute this amount not as equity, but as a loan to my company. In doing so, I take the same position as the bank: I become a creditor of Noé SA.

Initial balance sheet of the company

- Assets: real estate CHF 1,000,000

- Liabilities: bank debt CHF 750,000

- Liabilities: debt to the shareholder (me) CHF 150,000

- Equity (share capital): CHF 100,000

Private situation to be declare

- Loan to Noé SA: CHF 150,000

- Equity interest (shares) in the company: CHF 100,000

These are therefore the starting positions, both on the company side and the private side, from which we can now analyze the tax impact (profit/capital in the SA, income/wealth for the shareholder).

Step 4 — Letting your property through your company

The lease is signed, and your property starts generating income. The net rental result, after paying all expenses (maintenance, property taxes, interest, etc.), amounts to CHF 40,000, i.e. CHF 60,000 in rental income and CHF 20,000 in expenses.

At the end of the year, several options are available to you regarding how this profit can be used:

- Option 1 — Pay yourself part of the rental income to live on.

- Option 2 — As far as possible, repay the debt your company owes you.

- Option 3 — Once the debt has been repaid, pay yourself dividends.

- Option 4 — Retain the profit within your company to finance future real estate projects.

Each option has very different tax consequences, both for the company and for you in your private capacity.

Let’s now look in detail at what each of these options involves.

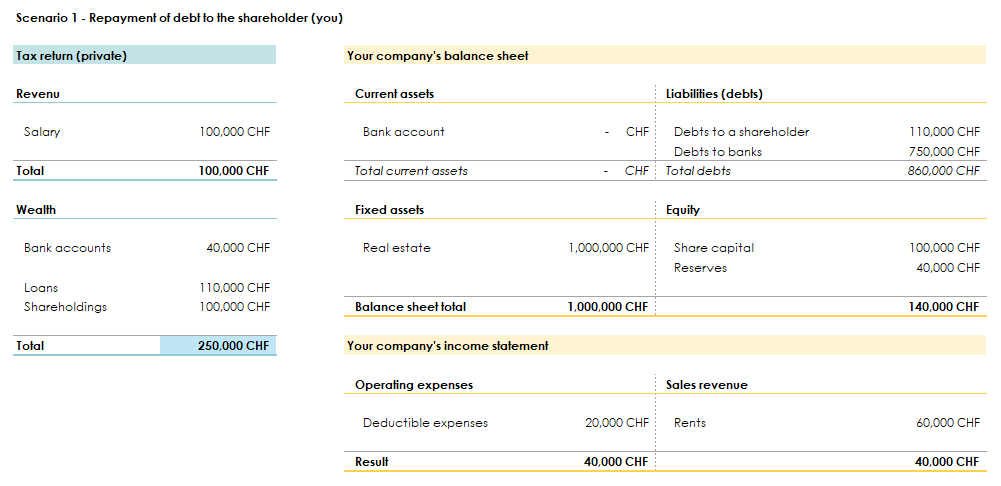

Option 1 — Reducing the debt your company owes you

In this first option, the objective is to transfer the rental income received by your company to your private account, while gradually reducing the debt your company has incurred in your favor.

Let’s look at how this works, both from a private perspective and from the company’s perspective:

Giving a full course in accounting and taxation in just a few lines would be ambitious, but here are the key points to remember:

- From a private perspective, your income and your wealth do not change. Indeed, a loan repayment is not considered taxable income. You will simply have CHF 40,000 more in your bank account, and your receivable from the company will decrease by the same amount. Result: an operation that is fiscally neutral (or almost).

- From the company’s perspective, the situation is just as straightforward: the CHF 40,000 received (rental income) is transferred almost immediately back to you, reducing the debt it owes you. In the end, the company’s accounts are empty, and its debt to you is reduced. Nevertheless, the company is accounting-wise “slightly richer,” as part of its debt has been repaid. This difference impacts, as a counterpart, its equity.

However, this example does not take into account a number of important details which, taken together, can affect taxation:

- Corporate taxes: a Swiss company that generates a profit must pay corporate income tax (on average between 13% and 15%). This tax is a deductible expense that reduces the CHF 40,000. In our example, this represents up to CHF 6,000.

- Tax valuation of your company: the value of your shareholdings (your shares) evolves over time. Initially, it corresponds to your CHF 100,000 of share capital, but the tax authorities regularly reassess this value using the practitioners’ method, which takes into account the company’s assets and profits. If the value of your company increases, your personal taxable wealth increases as well.

- Allocation to legal reserves: part of the profit (5%) must be allocated to legal reserves until these reserves reach 50% of the share capital. No distinction has been made in this article between free reserves and legal reserves.

- Right to repayment: some banks prohibit or limit the repayment of shareholder loans as long as their own mortgage loan has not been repaid. From the bank’s point of view, it does not want to be the only party bearing the risk.

- Accounting depreciation: it is possible to depreciate the property in order to create an additional accounting expense, which further reduces the taxable base.

- Actual (bank) amortization: in Switzerland, when a property is purchased with the minimum amount of equity, banks usually require amortization of part of the debt. In our example, the bank would theoretically accept that the debt is not repaid.

In summary, in my opinion, this is the best option if you wish to use the profits generated for private purposes. You can therefore receive around CHF 40,000 per year for four years without paying income tax, with the exception of approximately CHF 6,000 (around 15%) in corporate income tax payable by your company.

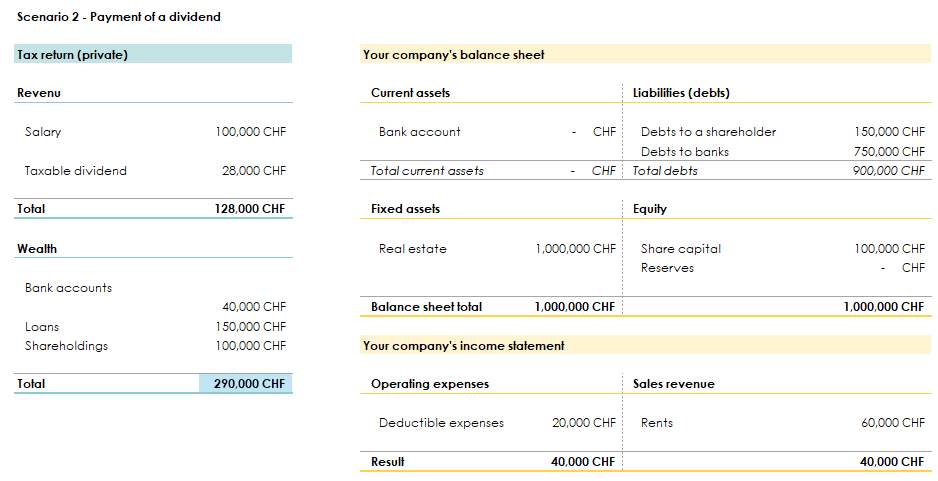

Option 2 — Paying yourself a dividend

This second option is based on a simple principle: if my company generates a profit, then—like any company—it can distribute a dividend to its shareholders, in this case, to me. To keep things clear and concise, we will omit certain technical steps (which we will detail later).

We are now at the beginning of the following year, and FBKConseils is handling my accounting. I inform them that I would like to receive CHF 40,000 in the form of a dividend.

Here is the result:

This article is starting to look like a “spot the difference” game! You’re looking at the same tables, but you have to identify what has changed. So let me help you: in this second option, almost nothing changes for the company. The debt, share capital, reserves and total balance sheet remain identical to the initial situation. In other words, the company still pays its CHF 6,000 in profit tax, just like in option 1, since dividends are not deductible from taxable profit.

On the private side, however, the situation changes significantly:

- Your taxable income increases, because you receive CHF 40,000 in dividends. However, you will not be taxed on the full amount, but only on CHF 28,000, thanks to the participation relief. In Switzerland, the cantons grant a tax reduction of 20% to 30% for shareholders holding more than 10% of a company’s share capital:

CHF 40,000 × 70% = CHF 28,000 taxable.

These CHF 28,000 are added to your salary and taxed at the ordinary rate. - From a wealth tax perspective, the company’s debt towards you remains unchanged (since it has not been repaid). However, you now have CHF 40,000 more in cash on your bank accounts. Result: an increase in your taxable wealth of CHF 40,000.

As mentioned earlier, several accounting and tax principles have deliberately been left aside to simplify the explanation:

- Allocation to legal reserves: as noted in option 1, part of the profit must be allocated to legal reserves. You therefore would not have been able to distribute the full CHF 40,000 as a dividend, but slightly less.

- Withholding tax (impôt anticipé): in Switzerland, any dividend distribution is subject to a mandatory 35% withholding tax, paid by the company to the tax authorities. You can recover this amount when filing your private tax return, by declaring that the tax has already been withheld at source.

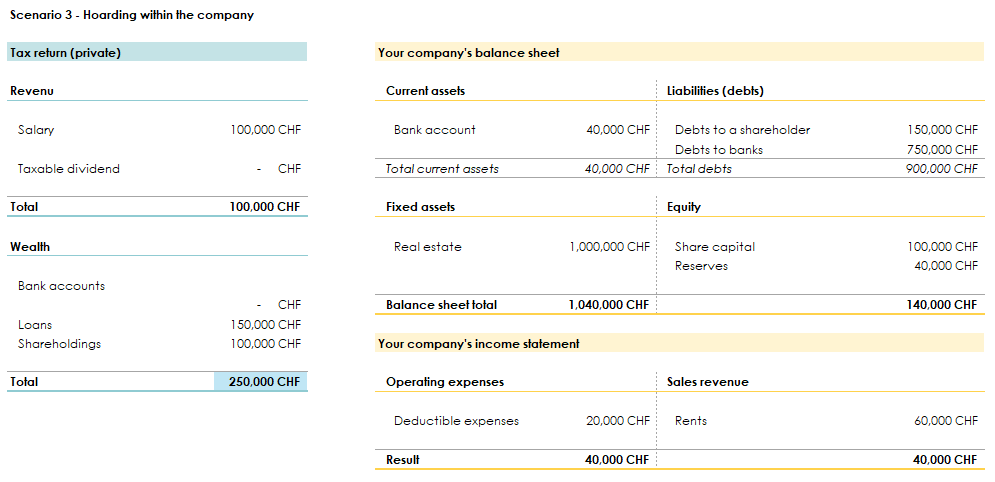

Option 3 — Pay yourself nothing at all

A real estate investment can serve two main objectives:

- Living off rental income (as seen above): you receive the cash and spend it, so the money must flow to your private bank account.

- Building long-term value: the rental income is not needed today but will be useful later. In this second case, the profits can simply remain within the company, without being distributed as dividends or used to repay shareholder loans. It is this second scenario that we will now examine.

Here is what this third option looks like:

The main advantage of using a company becomes clear here: if you do not need the funds in the short term, you simply leave them inside the company. The consequences are:

- you avoid personal income tax (linked to dividend distributions),

- you retain the company’s investment capacity to finance other projects (real estate or financial) when sufficient cash is available.

This structure is widely used by self-employed professionals and liberal professions whose activity generates significant savings but who already face high personal income tax rates. They invest through the company, build up reserves, and then, when their activity slows down or comes to an end, gradually pay out these reserves while maintaining a lower personal tax rate.

In short: if you do not need immediate cash, leaving profits within the company is often the most advantageous option, both fiscally and from a wealth-planning perspective.

Payment as salary

I have not discussed this option much, and I will not dwell on it either, because to be honest, I have never seen it applied in practice. However, in theory, you could pay yourself a salary from your own company. In return for the time spent managing it, you could pay yourself a salary of CHF 40,000.

In this case:

- The CHF 40,000 would be 100% taxable as personal income;

- It would also be subject to all social security contributions (AVS, AC, AI, LAA, LPP, etc.).

On the other hand, this salary would be deductible from the company’s taxable profit, thereby reducing its corporate income tax. This option could be particularly attractive if you wish to be affiliated with a second-pillar pension plan (LPP) and make pension buy-ins, which are fiscally advantageous. However, it remains to be seen whether the tax authorities would accept considering you an employee of a company that requires no real operational activity…

What is the most tax-efficient way to invest in real estate in Switzerland?

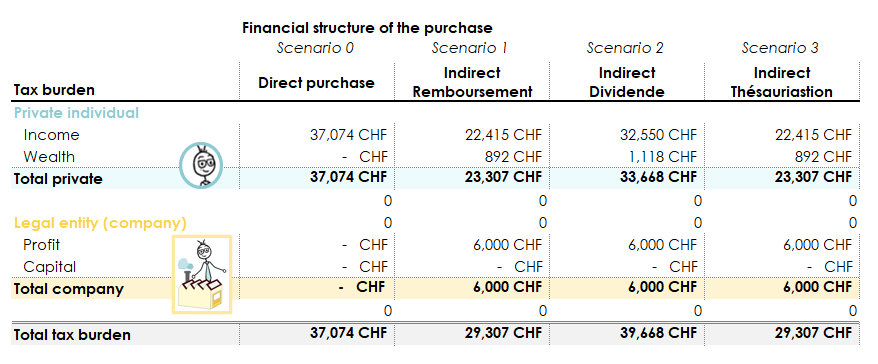

Now that we have examined direct private ownership, ownership via a company, and the different ways of extracting profits, the remaining question is straightforward: which solution is the most tax-efficient?

To compare them properly, let’s return to the same real estate project: a property purchased for CHF 1,000,000, generating CHF 60,000 in rental income with CHF 20,000 in expenses, located in the canton of Vaud.

Let’s take a moment to analyze this table, because it is undoubtedly the most important one in this entire article.

It is immediately clear that buying through a company and then paying yourself dividends is not tax-efficient. Why? Because there is double taxation:

- first, the company pays corporate income tax on its profit (around 15%),

- then, you pay personal income tax on the dividends received (even though the taxable base is not 100% of the dividend, but rather around 70%), without being able to treat this cash outflow as a deductible expense at the company level.

Result: this double layer of taxation significantly reduces the project’s profitability.

First conclusion: if you need the rental income to live on, do not buy through a company. Buy as a private individual instead: you avoid double taxation and, as a bonus, your wealth tax will probably be lower.

On the other hand, if you do not need the money immediately, setting up a company can be advantageous, particularly through retained earnings (leaving profits inside the company). With the figures from our example, this strategy saves around CHF 8,000 in tax per year, while at the same time building up capital for future investments. But be careful: retaining earnings does not mean escaping tax forever. Sooner or later, the money will have to leave the company. And if the amounts become too large, it may be difficult to spread withdrawals over a long period: you then risk falling back into high tax brackets. In short, retained earnings make sense in the short to medium term, but the exit strategy must be anticipated to avoid a painful tax catch-up later on.

To be honest, writing this article exhausted me! It’s long, technical, but I hope it was useful and practical for you. Before closing the chapter, let’s take a few more moments to touch on the sale of a property. In Switzerland, when it comes to real estate, taxes are everywhere: at purchase, during ownership, and of course… at sale. I’ll keep the explanations brief here, but I promise to come back to this topic in more detail in a future update.

Capital gains – a potential additional return… and tax at the time of sale

As in the first part of this article, it is important to distinguish two situations:

- those who purchased as private individuals (property held as private assets);

- those who set up a real estate company to hold the property.

Real estate capital gains on a property held privately

If everything goes as planned — and provided that the tax authorities do not reclassify you as a “professional real estate dealer” (we will come back to this point later) — the sale of your property will trigger a real estate capital gains tax, calculated in a relatively straightforward way:

Capital gain = Sale price – Purchase price – Capital expenditures

(costs and investments that increase the value of the property)

We therefore begin by determining the capital gain, by identifying its components:

Purchase price

This is simply the price paid at acquisition.

Sale price

This is the price at which the property is sold, after the holding period.

Transfer duties

A tax due at acquisition when ownership changes, generally between 3.5% and 5% of the purchase price.

Brokerage fees and commissions

If you use a real estate broker, their remuneration (approx. 2% to 4% of the sale price) is deductible.

Value-adding renovation costs and capital expenditures

These are value-creating works (swimming pool, major alterations, extensions, etc.). If they have not already been deducted as maintenance expenses from taxable income, they may be deducted from the capital gain for real estate capital gains tax (RECGT) purposes. Other costs may also be taken into account, such as financing costs or the acquisition of easements, etc.

Once the capital gain (taxable base) has been determined, the tax scale of the canton where the property is located is applied.

The tax rate depends in particular on the holding period: the longer the holding period, the lower the rate. As a general indication, rates typically range from around 2–3% (very long holding period) up to 30% (quick resale).

I mentioned this at the beginning, and believe me: despite the flattering title, it’s not something anyone would wish for. If the tax authorities consider, based on sufficient indicators (repeated transactions, profit-driven intent, level of organisation), that you buy and sell properties primarily to generate profits rather than for long-term asset management purposes, they may reclassify you as a “professional real estate dealer.”

The consequences are severe: the capital gain is no longer taxed under the real estate capital gains tax regime (with rates decreasing over time), but is instead included in your ordinary taxable income and taxed at your marginal tax rate (potentially around 40%), plus AVS social security contributions on the profit (around 10%). Altogether, the total burden can approach 50% (taxes plus social charges).

The real estate capital gain on a property held through a real estate company

Every time, I tell myself, “This time I’ll keep it simple”… and yet we could discuss this for hours, as there are so many special cases and variations in each situation. As always, I will therefore focus on what I consider to be the most common scenario. If I feel like it later on (or if tax law changes yet again), I may add further variants in a future update. And if you, on your side, would like to explore the topic in more depth, you can of course always book a first, no-obligation introductory meeting to continue the discussion with me.

In Switzerland, when it comes to selling real estate through a company, there are two types of transactions:

- Asset deal: this is a sale of assets (yes, another anglicism…). It means that you keep the company, but sell the property it owns.

- Share deal: this is a sale of shares. You sell the company as a whole, including everything it owns (real estate included), instead of selling the property separately.

In this article, we will focus on the asset deal scenario, i.e. the sale of a property owned by the company.

And to make things a bit more complex, not all Swiss cantons treat this transaction in the same way. They are divided between dualistic systems and monistic systems:

- Dualistic cantons: without diving back into Latin, “duo” does indeed mean “two,” because these cantons recognize two types of taxation:

- A real estate capital gains tax, identical to that applied to private individuals, with a degressive rate depending on the holding period (the longer you hold the property, the less tax you pay), as explained above.

- A corporate profit tax on the company.

- Monistic cantons: these apply only one method of taxation, whether the property is held by a private individual or by a company. In this case, real estate capital gains tax (as for private individuals) applies. This system is used mainly in the German-speaking cantons, with the exception of Jura, which also follows this model.

To conclude this article, let’s focus on an asset deal in a dualistic canton.

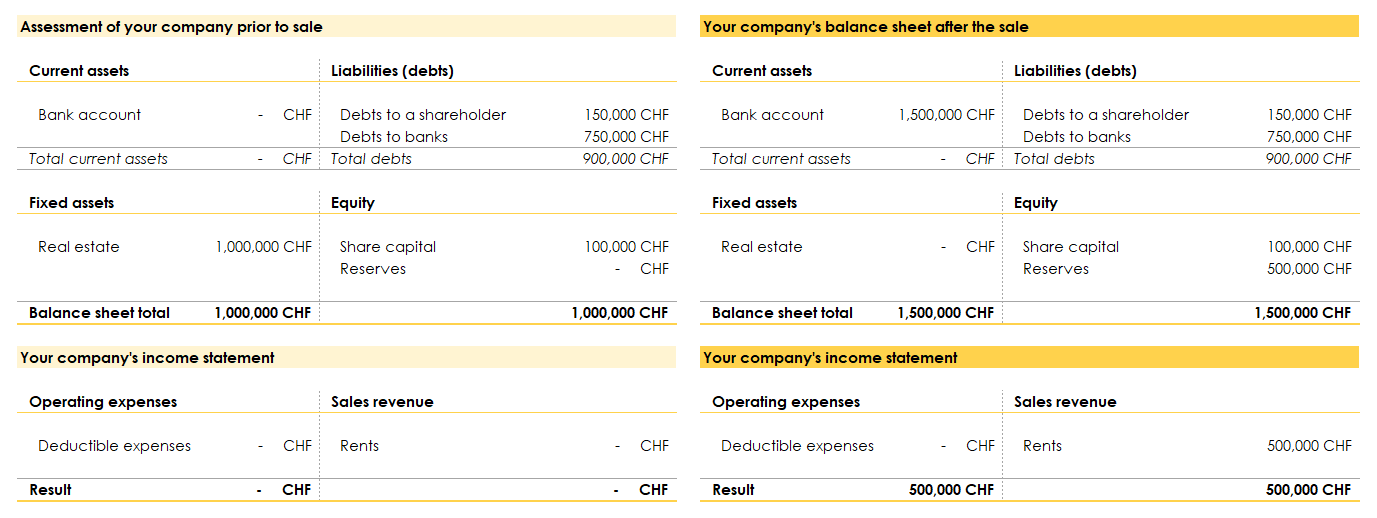

We will therefore return to our running example: in 2025, I purchase a property for CHF 1,000,000, financed by CHF 750,000 in mortgage debt, CHF 150,000 in a shareholder loan, and CHF 100,000 in equity. We are now in 2035. Life is good, real estate prices have risen, and the property is now worth CHF 1,500,000.

Let’s now see what happens from an accounting and tax perspective in this scenario.

Here, the key point to understand is that once the property is sold, the accounting capital gain between the book value and the sale price amounts to CHF 500,000. On this amount, the company must pay corporate profit tax (≈ 15%), which represents a tax charge of around CHF 75,000.

In conclusion: had I held the property as a private individual, I could have deducted more costs to reduce the taxable base (the capital gain) and, after a long holding period, been taxed at around 3% — compared to 15% when held through a company. The difference is substantial.

All right, I suggest we stop here for today. And since everything is already written, let me take a moment to explain briefly how my firm can help you…

How FBKConseils can help you with your real estate project and your taxes?

Introductory meeting

Taking 20 minutes to answer your questions and introduce ourselves is, in our view, the best way to get to know each other and see whether our firm can support you with your current and future projects. That’s why we offer a free introductory meeting, either in person at our offices or by video conference, at a time that suits you.

Tax and financial simulations

Between the moment you consider investing and the moment you actually take action, time often passes. During this period, we carry out all the tax and financial simulations needed to eliminate grey areas and reduce the uncertainties surrounding your project.

Company formation

If, after reading, you decide to opt for the creation of a company (real estate company / SA / Sàrl), our firm will take care of all the steps: articles of association, bank account opening, registrations, tax options, initial accounting setup, and more.

Accounting and tax management

This is the core business of a fiduciary firm: we handle your accounting, prepare your tax returns (both corporate and personal), and ensure consistency between the company side and your private situation.

Real estate financing

FBKConseils can also support you with financing matters: equity, mortgages, amortization, loan terms, and reviewing bank offers, helping you secure your decisions and optimize your costs.