Written by Yanis Kharchafi

Written by Yanis KharchafiUpdated on July, 16th 2025.

Everything you need to know about wealth tax in Switzerland

Introduction

Before diving into the heart of the topic, let’s take a step back. This time, we won’t focus solely on what’s happening around Lake Geneva. Why this approach? Because at our fiduciary, we often meet clients with strong preconceived notions about wealth tax.

Some consider it a straightforward case of double taxation. Others see it as a covert way for the State to keep tabs on what taxpayers do with their money. And finally, for a third group, this tax represents a fair way to make those with significant wealth contribute in line with their actual means.

All of this shows that—unlike income tax—wealth tax is a subject of controversy, which is precisely why I’d like to explore it more deeply with you today.

Before going any further, an important clarification: at FBKConseils, we’ve created detailed, canton-specific articles on this tax. These explain exactly how wealth tax is calculated and what rates apply:

- Wealth Tax in the Canton of Vaud

- Wealth Tax in the Canton of Geneva

- Wealth Tax in the Canton of Valais

In this article, my goal is to give you a better understanding of how this tax works in general, so you can better assess its real impact on your overall tax burden.

The line-up:

Is Switzerland an exception when it comes to wealth tax?

Without claiming to master all the nuances of global taxation, a quick search is enough to confirm that wealth tax is indeed a vanishing species. Over the past 30 years, many countries have gradually decided to abolish this type of tax. In practice, taxing wealth is not always seen as fair—and more importantly, it’s a particularly complex measure to implement and sustain:

Tax evasion

It has become relatively easy for some taxpayers to hide assets from tax authorities, despite the progress made with automatic exchange of information. In reality, many countries aren’t fully cooperating, or have other priorities for now.

High administrative costs

This point ties directly to the previous one: the greater the risk of tax evasion, the more resources are required for audits and enforcement. Studies show that it’s often lower-income taxpayers who get flagged for (usually unintentional) errors, while wealthier individuals have more tools at their disposal to hide—or let’s say, “optimize”—their holdings. Considering that wealth tax often brings in only a small fraction of total tax revenues, many countries choose to phase it out entirely.

Challenges in valuing taxable assets

Cash is easy to value. But what about real estate—should you use the purchase price, market value, or insurance value? And what about digital assets that fluctuate daily? How do you value privately held businesses? What exchange rate do you apply for foreign currencies—the year-end rate or an annual average? These are just a few of the many questions that make accurately calculating wealth tax highly complex.

For these reasons—and likely others—only three European countries still apply a general wealth tax today: Spain, Norway, and Switzerland.

France, for instance, now only levies a real estate wealth tax (IFI), which applies solely to real estate assets valued over €1.3 million. All other types of assets are exempt.

In conclusion?

Wealth tax is clearly on the decline. While it may seem inexpensive for taxpayers in theory, in practice it brings more complications than benefits for the states that continue to enforce it.

Who has to pay wealth tax in Switzerland?

Before diving into numbers, rates, and tax optimization, it makes sense to start with a basic question: are you even subject to this tax?

In Switzerland, all taxes must be clearly grounded in law—and thankfully, they are.

For wealth tax, the legal foundation is laid out in the Federal Act on the Harmonization of Direct Taxes of Cantons and Municipalities (FTHA). This law defines the rights and obligations of cantons and municipalities regarding taxation. If you’re a thorough reader and clicked on the link, you didn’t need to go far: by Article 2, it already states that “the cantons levy the following taxes: a tax on income and a tax on the wealth of individuals.”

In other words, all Swiss cantons—yes, even the friendliest ones—are required to levy a small tax on your assets.

That said, the same law clarifies right from Article 1 that “the determination of tax scales, rates, and exempt amounts remains the responsibility of the cantons.”

In summary: Whether you live in the heart of Geneva or right next to the ski slopes, wealth tax will apply to you. However, as we’ll see later, each canton has some flexibility to exempt a portion of your assets or to apply more or less favorable tax scales, depending on the social and fiscal policies it chooses to promote.

A Quick Side Note: There are two notable exceptions to this general rule:

- First, foreign nationals working for certain international organizations or diplomatic missions, provided their assets consist only of movable property (e.g., bank accounts, securities).

- Second, taxpayers who have negotiated a lump-sum tax agreement (commonly known as a “forfait fiscal”) directly with their canton.

What assets are taxable under Swiss wealth tax?

Here comes the moment of truth: in Switzerland, absolutely everything you own is subject to wealth tax. The rule is straightforward and non-negotiable: the tax authorities must know the full value of your assets as of December 31st of each tax year.

Based on this simple principle, you’ll be required to report the precise value of the following assets in your tax return:

- Your bank accounts: A quick note—bank accounts fall under movable assets and are always taxed at your place of residence, whether the funds are in Switzerland or abroad.

- Cash on hand: Here’s a real-world anecdote—some clients ask us at year-end whether they should withdraw CHF 50,000 and stash it under the mattress so that their bank statement shows a balance of CHF 0. The answer is simple: no, and here’s why.

First, in most cantons, CHF 50,000 generates almost no tax liability. Second, even if the money is withdrawn, it must still be reported as cash in your tax declaration; otherwise, it’s considered tax fraud. - Stock market investments: This includes shares, bonds, equity stakes, investment funds, ETFs, and similar instruments.

- Real estate: Whether located in Switzerland or abroad, all properties must be declared.

- Valuable personal property: Think watches, fine wines, collector cars, jewelry, and works of art.

- Cryptocurrencies and digital assets: Yes—even your crypto holdings must be reported and are fully subject to wealth tax.

- Equity in private businesses: If you own a stake in a company, it counts too.

By now, the message should be crystal clear: you are expected to report your full net worth as accurately as possible—year after year.

Debt as a tool to reduce your taxable wealth

While you do need to declare all of your assets, Switzerland only taxes your net wealth. Net wealth is simply the total value of your assets as of December 31st, minus all your debts on that same date.

When people in Switzerland think about debt, they often jump straight to mortgages. However, debt can take many forms, all of which may reduce your taxable wealth:

- Mortgage loans: The most common type of deductible debt in Switzerland.

- Student loans: Less common in Switzerland but very common in English-speaking countries. These are also considered deductible debts.

- Private loans: If you borrowed money from your partner to help grow your shared wealth, the borrowed amount must be listed as a debt in your declaration. Your partner, in turn, must report it as a personal receivable.

- Credit card debt: If you owe money to your credit card company as of December 31st, that balance is deductible from your taxable wealth.

- Consumer loans: These include personal loans taken out to finance purchases such as cars, furniture, or electronics.

- Tax debts: If you haven’t paid enough in tax prepayments—or worse, if you haven’t paid anything—you have a debt toward the tax office as of December 31st. This situation can also apply to people taxed at source (e.g. married couples under “scale C” where both spouses have income), if too little has been withheld throughout the year.

How much does the Swiss wealth tax cost you?

We’ve finally made it! After nearly 2,000 words, you’re about to find out—hopefully—how much your wealth, whether in real estate, stock investments, or other assets, will cost you each year in Swiss wealth tax.

Wealth tax – A Cantonal and Communal matter

If you’ve been following us through our articles or on our YouTube channel, you probably already know that the Swiss tax system operates on multiple levels:

- The Confederation

- The canton of residence

- The municipality of residence

Each of these three levels can decide how heavily (or lightly) to tax your income, wealth, or other elements. But when it comes specifically to the wealth tax, only cantons and municipalities have the authority to levy it. The Confederation, for its part, has chosen not to tax wealth at all.

With that in mind, it’s essential to understand that both cantons and municipalities have significant flexibility in setting their own tax brackets and rates. In other words, depending on whether you live in Zug or Geneva, your tax burden can vary greatly.

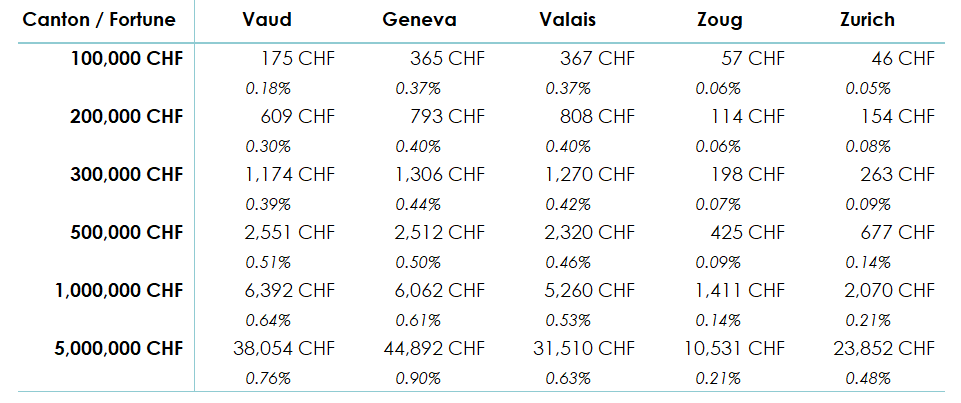

Let’s illustrate this with a few numbers from five representative cantons:

What can we take away from this table full of numbers, which aren’t always easy to understand?

- The French-speaking cantons apply significantly higher wealth tax rates than the German-speaking cantons. For example, the wealth tax in Geneva can be up to 4.5 times higher than in the canton of Zug.

- Between the cantons of Vaud, Valais, and Geneva, the tax levels remain relatively similar. In other words, moving to Valais just to save on wealth tax is not necessarily the most effective strategy.

- Even in the most expensive cantons in French-speaking Switzerland, the wealth tax remains moderate, generally ranging between 0.18% and 1% at most.

The impact of the municipality on wealth tax in Switzerland

After examining five cantons and drawing more or less comprehensive conclusions, there remains, in my opinion, an important factor to consider: the impact of your municipality of residence on your overall taxation.

As previously mentioned, only the cantons and municipalities have the authority to tax your wealth. We have also observed that differences between cantons can be significant. However, what we have not yet clearly stated is that, to establish the previous table, we preselected a representative municipality within each canton: Lausanne for the canton of Vaud, the city of Geneva for the canton of Geneva, Sion for the canton of Valais, and so on. This choice necessarily influenced the total tax burden.

In concrete terms, this means that if we had chosen, for example, the municipality of Rossinière (the most expensive in the canton of Vaud) or the municipality of Genolier (one of the least expensive in the same canton), the results could have varied significantly. Here is what that might look like for the canton of Vaud (this logic naturally applies to all other cantons as well):

En conclusion, entre Rossinière et Genolier, un contribuable disposant par exemple d’un patrimoine de CHF 5’000’000 économiserait plus de CHF 4’500 sur ses impôts annuels liée uniquement à la fortune, soit environ 12 % du montant total de cet impôt. Une différence loin d’être négligeable.

Wealth tax in Switzerland – Is it Possible to optimize it?

To wrap up this article nicely, and knowing that readers of this kind of content usually want to better manage their taxes, the natural question arises: are there ways to optimize wealth tax in Switzerland (of course, always legally)?

Let’s be honest: if optimizing income tax is already no small feat, optimizing wealth tax is even more limited. However, I’ll suggest a few interesting avenues — but keep in mind that each comes with important trade-offs to carefully consider before taking action.

Buying real estate personally in Switzerland

If you buy a property directly, that is, without going through a real estate company, it is likely that the “tax value” used by the cantonal tax authorities will be significantly lower than the actual purchase price and the market value of the property. Concretely, you could buy a property for CHF 1,000,000 and see it declared in your tax return at a value between CHF 400,000 and CHF 800,000 depending on the location and the canton.

If you combine this purchase with a mortgage debt, you can even manage to significantly reduce the taxable portion of your wealth.

Buying real estate personally abroad

Without going into all the technical details, keep in mind that in international taxation, real estate properties are always taxed abroad at their location. Concretely, if you buy a property in the charming city of Essaouira, Morocco, this property will no longer be taxable in Switzerland but in Morocco. If Morocco decides not to tax real estate wealth (this is an example and should be verified), then this portion of your assets disappears from Swiss taxation.

An important clarification: even though this property is no longer taxable in Switzerland, it still remains taken into account (“determinant”) for calculating the tax rate applicable to your other income or assets in Switzerland.

Making Buy-Ins to your 2nd pillar (LPP)

In Switzerland, generally, retirement assets—whether in the 2nd pillar (LPP) or the 3rd pillar—are not subject to wealth tax as long as they remain locked in these schemes. Consequently, making voluntary buy-ins to your 2nd pillar not only directly reduces your taxable wealth but also lowers your taxable income in the year of the contribution. A win-win optimization.

To be honest, going further with examples here may not be relevant, as your situation is unique and deserves individual analysis. There are probably other options worth considering depending on your personal circumstances.

If you have an idea or a question about a specific case and want to know our opinion, don’t hesitate to send us an email at: [email protected].

FAQ: Wealth tax in Switzerland

Are foreigners or residence permit holders also subject to wealth tax?

Yes, the same rules apply whether you are a Swiss citizen, hold a C permit, or even a B permit. Although you may be taxed at source, as soon as your net wealth exceeds the taxable threshold, you must file a subsequent ordinary taxation (Taxation Ordinaire Ultérieure, TOU) and pay the corresponding wealth tax.

Does marriage affect wealth tax?

In principle, no. However, each canton has its own specific rules. In most cases, cantons simply combine the spouses’ assets and tax them as a single net wealth according to the ordinary scale.

How to value real estate in Switzerland?

Good news: for all real estate located in Switzerland, your canton’s land registry can provide the exact value to declare in your tax return. Some cantons apply specific rules: for example, Vaud or Valais use their own fiscal valuation methods, whereas Geneva starts from the original purchase price and applies a deduction based on the holding period.

How to value real estate abroad?

It depends on your canton of residence. Each canton applies internal rules generally based on the original purchase price, without considering the current market value. In some exceptional cases, cantons may accept the official tax valuation of the country where the property is located, which can make a notable difference.

Which exchange rates should be used for foreign assets?

The Federal Tax Administration (FTA) and cantonal tax authorities update every year the official conversion rates to convert your assets held in foreign currencies. If there is an error, the cantonal tax office will generally correct it themselves.

How to value shares in unlisted companies?

It is common to invest in SMEs whose shares have no official market value. In such cases, cantons generally apply the practitioners’ method, which takes into account the company’s equity as well as the average profits over the last three years.

What happens in case of omissions or errors in previous tax declarations?

It is quite common to forget to declare a foreign bank account, a rental guarantee, or even a property. The tax authorities allow taxpayers to voluntarily correct these omissions or errors without penalties or fines, but only once. This specific procedure is called spontaneous disclosure.

How FBKConseils can help you with your taxes and wealth?

An introductory meeting

At FBKConseils, we offer you a first free consultation of about twenty minutes. The goal of this meeting is to clearly answer all your questions and, if necessary, explain our approach and how we work.

Personalized tax simulation

Whether you are considering moving to Switzerland, have received a significant sum of money, or plan to purchase real estate, we can assist you by providing precise tax simulations. The objective? To concretely assess the impact of these changes on your overall taxation, so you can anticipate and better manage your tax burden.

Tax declaration in Switzerland

Like any professional fiduciary, FBKConseils supports you at every stage of the tax process. We offer our clients two ways to complete their tax declaration: either together, directly in our offices in Lausanne, or more traditionally remotely, simply by securely sending your documents.